The Revolution Will Not Be Funded (Excerpts)

Republished with added images by Warrior Publications

December 22, 2016

It’s time to liberate activists from the nonprofit industrial complex

Excerpts from the book The Revolution Will Not Be Funded

The nonprofit system has tamed a generation of activists. They’ve traded in grand visions of social change for salaries and stationery; given up recruiting people to the cause in favor of writing grant proposals and wooing foundations; and ceded control of their movements to business executives in boardrooms.

This argument—that reformers have morphed into cogs in the nonprofit industrial complex—is explained and explored in the fiery anthology The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex, edited by the INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence collective (South End, 2007).

One piece of the puzzle: “Foundations provide tax shelters for wealthy families and thereby take away tax income that could be used for social programs and entitlements,” Andrea J. Ritchie, an INCITE! member, told Make/shift. “And then [the foundations] dole out little bits of money for nonprofits to replace the services that the government no longer funds.”

The book brings together 21 experienced radical activists to explore the shortcomings of nonprofits as movement makers; here are excerpts from three chapters.

—The Editors of Utne Reader

Adjoa Florência Jones de Almeida

Sista II Sista Collective, Brooklyn, New York

What has happened to the great civil rights and black power movements of the 1960s and 1970s? Where are the mass movements of today within this country? The short answer: They got funded. Social justice groups and organizations have become limited as they’ve been incorporated into the nonprofit model. We as activists are no longer accountable to our constituents or members because we don’t depend on them for our existence. Instead, we’ve become primarily accountable to public and private foundations as we try to prove to them that we are still relevant and efficient and thus worthy of continued funding.

In theory, foundation funding provides us with the ability to do the work—it is supposed to facilitate what we do. But funding also shapes and dictates our work by forcing us to conceptualize our communities as victims. We are forced to talk about our members as being “disadvantaged” and “at risk,” and to highlight what we are doing to prevent them from getting pregnant or taking drugs—even when this is not, in essence, how we see them or the priority for our work.

And what are our priorities? Perhaps the real problem is that we don’t spend enough time imagining what we want and then doing the work to sustain that vision. That is one of the fundamental ways the corporate-capitalist system tames us: by robbing us of our time and flooding us in a sea of bureaucratic red tape, which we are told is a necessary evil for guaranteeing our organization’s existence. We are too busy being told to market ourselves by pimping our communities’ poverty in proposals, selling “results” in reports and accounting for our finances in financial reviews.

In essence, our organizations have become mini-corporations, because on some level, we have internalized the idea that power—the ability to create change—equals money.

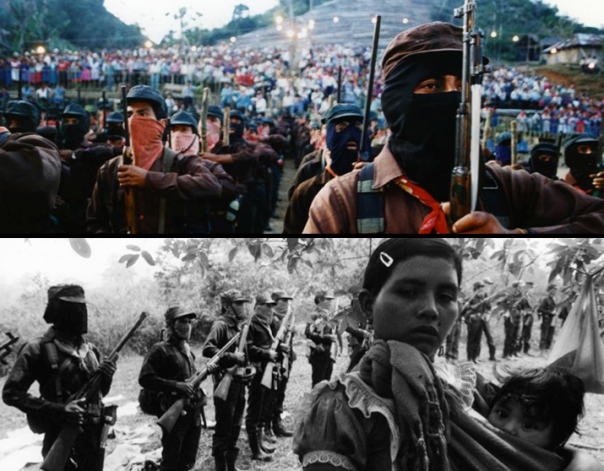

Zapatistas in formation. Top: Juan Popoca / Bottom: Ángeles Torrejón

If nonprofit jobs are the only spaces where our communities are engaged in fighting for social justice and creating alternatives to oppressive systems, then we will never be able to engage in radical social change. Would the Zapatistas in Chiapas or the Landless Workers Movement members in Brazil have been able to develop their radical autonomous societies if they had been paid to attend meetings and to occupy land? If these mass movements had been their jobs, it would have been very easy to stop them by merely threatening to pull their paychecks.

In this country, our activism is held hostage to our jobs—we are completely dependent on a salary structure, and many of us spend over half of our staff hours struggling to raise salaries instead of creating real threats and alternatives to the institutional oppression faced by our communities. Meanwhile, the imaginative and spiritual perspective that would allow us to question the “givens” dictated by neoliberalism begins to erode.

Amara H. Pérez

Sisters in Action for Power, Portland, Oregon

Foundations are ultimately interested in the packaging and production of success stories, measurable outcomes, and the use of infrastructure and capacity-building systems. As nonprofit organizations that rely on foundation money, we must embrace and engage in the organizing market. This resembles a business model in that the consumers are foundations to which organizations offer to sell their political work for a grant. The products sold include the organizing accomplishments, models, and successes that one can put on display to prove competency and legitimacy. In the “movement market,” organizations competing for limited funding are, most commonly, similar groups doing similar work across the country. Not only does the movement market encourage organizations to focus solely on building and funding their own work, it can create uncomfortable and competitive relationships between groups most alike—chipping away at any semblance of a movement-building culture.

Over time, funding trends actually come to influence our work, priorities, and direction as we struggle to remain competitive and funded in the movement market. For many activists, this has shifted the focus from strategies for radical change to charts and tables that demonstrate how successfully the work has satisfied foundation-determined benchmarks.

Madonna Thunder Hawk

Cheyenne River Sioux reservation, South Dakota

Women of All Red Nations (WARN) had tax-exempt status once, but we let it lapse. It was too complicated. No one wanted to sit in the office and write reports with time and energy that could be used to advance our movement.

How we organized was different from how activists tend to respond now. We didn’t wait for permission from anyone. We didn’t have people tell us, this is too big of a project for you to do—you should contact the state or some other governing power first. Nowadays, an organization might want to do something more creative, but its board of directors will tell them no. We did not worry if our work would upset funders; we just worried about whether the work would help our communities.

Mi’kmaq warriors at a tire fire blockade on Hwy 11, Dec 2, 2013, during resistance to SWN exploratory work for fracking.

Before, we focused on how to organize to make change, but now most people will only work within funding parameters. People work for a salary rather than because they are passionate about an issue. When you start paying people to do activism, you can start to attract people to the work who are not primarily motivated by or dedicated to the struggle. In addition, getting paid to do the work can also change those of us who are dedicated. Before we know it, we start to expect to be paid and do less unpaid work than we would have before. This way of organizing benefits the system, of course, because people start seeing organizing as a career rather than as involvement in a social movement that requires sacrifice.

As a result, organizing is not as effective. For example, we first started organizing around diabetes by analyzing the effects of government commodities on our health: Indian communities were given unhealthy foods by the government in exchange for our having been relocated from our lands, where we engaged in subsistence living, and now damming and other forms of environmental destruction affect our ability to be self-sustaining. Today you can get a federal grant to work on diabetes prevention, but rather than get the community to organize around the politics of diabetes, people just sit in an office all day and design pamphlets. Activism is relegated to events. Many people will get involved for an event, but avoid rocking the boat on an ongoing basis because if they do, they might lose their funding. For instance, if the government is funding the pamphlet, then an organization is not going to address the impact of U.S. colonialism on Native diets because they don’t want to lose funding.

Activism is tough; it is not for people interested in building a career.

Excerpted from The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex, edited by Incite! Women of Color Against Violence, South End Press 2007