Nov 20

20110

Carbon Markets | REDD, Democracy Centre, The International Campaign to Destabilize Bolivia

Bolivia CIDOB | Confederation of Indigenous People of Bolivia Morales REDD TIPNIS USAID

Bolivia: Solidarity Activists Need to Support Process

Sunday, November 20, 2011 | Green Left Weekly

Bolivia’s first indigenous president celebrates winning a recall referendum in August 2008.

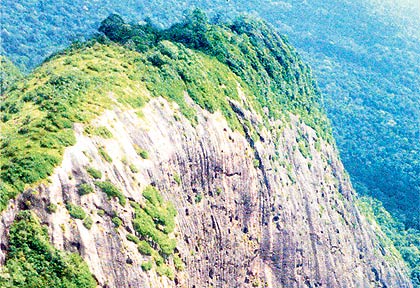

The recent march in Bolivia by some indigenous organisations against the government’s proposed highway through the Isiboro Secure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS) has raised much debate among international solidarity activists.

Such debates have occurred since the election of Bolivia’s first indigenous president, Evo Morales, in 2005 on the back of mass uprisings.

Overwhelmingly, solidarity activists uncritically supported the anti-highway march. Many argued that only social movements — not governments — can guarantee the success of the process of change.

However, such a viewpoint is not only simplistic; it can leave solidarity activists on the wrong side.

Kevin Young’s October 1 piece on Znet, “Bolivia Dilemmas: Turmoil, Transformation, and Solidarity”, tries to grapple with this issue by saying that “our first priority [as solidarity activists] must be to stop our governments, corporations and banks from seeking to control Bolivia’s destiny”.

Yet, as was the case with most articles written by solidarity activists, Young downplays the role of United States imperialism and argues the government was disingenuous in linking the protesters to it.

Others went further, denying any connection between the protesters and US imperialism.

The Confederation of Indigenous Peoples of the Bolivian East (CIDOB), the main organisation behind the march, has no such qualms. It boasted on its website that it received training programs from the US government aid agency USAID.

On the site, CIDOB president Adolfo Chavez, thanks the “information and training acquired via different programs financed by external collaborators, in this case USAID”.

Ignoring or denying clear evidence of US funding to such organisations is problematic. Attacking the Bolivian government for exposing this, as some did, disarms solidarity activists in their fight against imperialist intervention.

But biggest failure of the solidarity movement has been its silence on US and corporate responsibility for the conflict.

The TIPNIS dispute was not some romanticised, Avatar-like battle between indigenous defenders of Mother Earth and a money-hungry government intent on destroying the environment.

Underpinning the conflict was the difficult question of how Bolivia can overcome centuries of colonialism and underdevelopment to provide its people with access to basic services while trying to respect the environment. The main culprits are not Bolivian; they are imperialist governments and their corporations.

We must demand they pay their ecological debt and transfer the necessary technology for sustainable development to countries such as Bolivia (demands that almost no solidarity activists raised). Until this occurs, activists in rich nations have no right to tell Bolivians what they can and cannot do to satisfy the basic needs of their people.

Otherwise, telling Bolivian people that they have no right to a highway or to extract gas to fund social programs (as some NGOs demanded), means telling Bolivians they have no right to develop their economy or fight poverty.

Imperialism aims to keep Third World nations subordinate to the interests of rich nations. This is one reason foreign NGOs and USAID are trying to undermine the Morales government’s leading international role in opposing the grossly anti-environmental policies, such as Reduce Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD).

REDD uses poor nations for carbon offsets so corporations in rich countries can continue polluting. Support for REDD was one of the demands of the protest march.

Young says “our solidarity should be with grassroots revolutionaries, anti-imperialists and defenders of human rights, not with governments or parties”.

But, as the TIPNIS case shows, when governments are trying to grapple with lifting their country out of underdevelopment, the demands of social movements with competing sectoral interests may clash.

In fact, some of the most strident supporters of the highway were also the very same social movements that solidarity activists have supported in their struggles against neoliberal governments during the last decade.

In such scenarios, you can only choose between supporting some social movement demands by dismissing legitimate demands of others, as many did with the TIPNIS case.

Lasting change can only come about when social movements begin to take power into their own hands when social movements become governments.

It is this objective that Bolivia’s social movements set. They forged their own political instrument through struggle ? commonly known as the Movement Towards Socialism ? and won a government they see as their own.

Having gone from a position of “struggle from below” to taking government from the traditional elites as an instrument to achieve their goal of state power, these social movements have begun winning control over natural resources and enacted a new constitution.

Converting the constitution’s ideals into a new state power remains a task for the Bolivian revolution.

But its success depends on the ability of “grassroots revolutionaries, anti-imperialists and defenders of human rights” ? operating within and without the existing state ? to struggle in a united way.

Our solidarity must be based on the existing revolutionary struggle in Bolivia, not a romanticised one we would prefer.

A permanent state of protests may be attractive for solidarity activists, but ultimately can only translate into a permanent state of demoralisation unless social movements can go beyond opposing capitalist governments and create their own state power.

Refusing to support the struggles as they exist illustrates a lack of confidence in the Bolivian masses to determine their own destiny. It also displays an arrogance on the part of those who, having failed to hold back imperialist governments at home, believe they know better than the Bolivians how to develop their process of change.

Mistakes are made in any struggle. But such mistakes should not be used to try and pit one side against another. We should have confidence that these internal conflicts can be resolved by the social movements themselves.

[Federico Fuentes edits Bolivia Rising.]