Apr 23

20100

Environmental Defence Fund, National Wildlife Federation, Nature Conservancy, Sierra Club

and National Wildlife Foundation Center for Biological Diversity Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) James Hansen Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) Policy Sierra Club The Nature Conservancy USCAP

COMMON DREAMS | Mainstream Green Groups Cave In on Climate

Note – This article has been endorsed by James Hansen.

Published on Tuesday, April 20, 2010 by CommonDreams.org

Mainstream Green Groups Cave In on Climate

Dangerously Allow Industry to Set Agenda

by Gary Houser and Cory Morningstar

“Governments will not put young people and nature above special financial interests without great public pressure. Such pressure is not possible as long as big environmental organizations provide cover. So the best hope is this — individuals must demand that the leaders change course or they will lose support.” – Dr. James Hansen

With climate scientists warning that we are in a global emergency and tipping points leading to runaway catastrophe will be crossed unless carbon pollution is rapidly reduced, one would expect groups identified as environmental defenders to be shifting into high gear. Instead, we are witnessing the unspeakably tragic spectacle of a mainstream environmental movement allowing itself to be seduced and co-opted by the very forces it should be vehemently opposing. At the very moment when moral leadership and courage are needed the most, what we see is a colossal failure of both – with potentially irreversible consequences for our civilization. If Congress chooses an inadequate response to the crisis, policies can get “locked in” which virtually guarantee that these tipping points are crossed. These organizations are using their significant financial resources to create a public impression that the “environmental community” has given its “stamp of approval” to this policy and to marginalize the voices of the genuine grassroots activists who represent the heart and soul of the climate movement. With nothing less than the future of the planet at stake, these groups must now be publicly challenged and held accountable for their actions.

The stage has been set for this necessary debate by publication of Johann Hari’s excellent commentary entitled “The Wrong Kind of Green“. In this piece, Hari provides important insight into some of the relevant history. He describes how in the 1980s and 1990s some of the larger environmental groups began to adopt a policy often called “corporate engagement”. The basic idea was that by participating in “partnerships” with corporations – some involving receipt of monetary contributions – there would be opportunity to exert positive influence.

It is not possible to look into the minds of those who promoted this shift. Perhaps there was a sincere hope that corporations would be moved toward more responsible behavior. Whatever the case, the critically important task at this time is not to evaluate possible motives but rather the real life consequences. To do so honestly, all self-interested blinders must be set aside.

The truth is that this policy has created a “slippery slope” leading to severely compromised stances – nowhere more apparent than in regard to the over-arching issue of climate. In 2007, a coalition was formed between corporations and environmental organizations called the U.S. Climate Action Partnership, or USCAP – whose purpose was to influence U.S. climate legislation. Some of the large groups that joined were Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), the Nature Conservancy, and National Wildlife Foundation. In January 2009, USCAP presented its proposals and these became the framework of the Waxman-Markey bill.

The physical context is that previously projected worst case scenarios are already being surpassed and humanity is running out of time. Ice is melting far more rapidly than expected, releasing the “albedo effect” where open water absorbs more heat and accelerates further melting. The normally quite cautious National Science Foundation is ringing alarm bells about the methane – a greenhouse gas over 30 times as powerful as CO2 – now venting from the Siberian seabeds. According to the NSF statement: “Release of even a fraction of the methane stored in the shelf could trigger abrupt climate warming.” These are only two examples of “reinforcing feedbacks” that can significantly move the process closer to tipping points.

Within a context so dire that in reality a war-time level of mobilization is needed, what kind of legislation is being offered? First of all, the emission reduction targets themselves – apart from the theoretical strategies for achieving them – categorically ignore the science. The goals do not even aim at stabilization at 350 ppm (let alone the lower figures more likely to be necessary) and the time frame for enacting meaningful reductions is not even remotely close to the speed needed to prevent disaster.

Beyond the issue of targets is that of reduction strategies. USCAP would like to see a trillion dollar carbon market put into place, where traders can claim “pollution rights” to the sky and seek profits from the exchange of such “rights”. Such a system – which would determine whether life-supporting ecosystems survive or collapse – would be placed into the same manipulative hands on Wall Street that brought on the financial meltdown. As this commentary goes to press, several traders in the European carbon market (the world’s prototype) have been arrested in connection with a ), NRDC and EDF are sending their own people to promote it at carbon trade conferences.

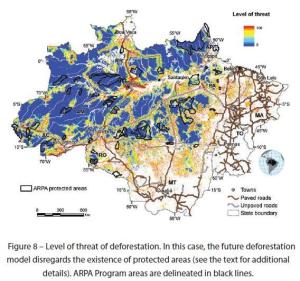

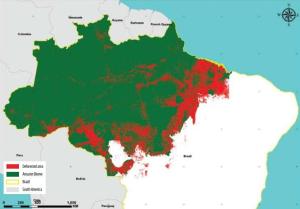

The next immoral concession is to allow the industry to “buy” its way out of actually reducing emissions by supporting so-called “offsets” – such as forest preservation projects in the developing world. Sounding plausible in theory, offsets are actually riddled with verification issues and defects such as loggers simply moving elsewhere. But the bottomline “wrong” here is that any form of offsetting should never be looked at as an alternative to reducing emissions. It should only be seen as an additional action to take.

Then there is the unbelievable capitulation represented by the removal of EPA authority to regulate coal-burning. Now that the EPA has finally been empowered by the Supreme Court to act against a carbon-fueled ecocide, this ability has been effectively stripped from the House bill without a murmur from the USCAP “greens”. The result of all these concessions is a pathetically weak bill that the Congressional Budget Office estimates will not even begin to reduce emissions until 2018. Other studies indicate that if all available offsets are used, reductions could actually be postponed an astonishing 19 years until 2029.

The USCAP “greens” proclaim that their positions are being driven by “political expediency”. But there is a stunning “disconnect” which these groups have been reticent to address. How does one negotiate with a melting iceberg? Can the inexorable laws of physics be placed “on hold” while emission reductions are scuttled in a process of political “horse-trading”? What is the meaning of “expediency” when it leads to the collapse of society as we know it? John Schellnhuber, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Reseach, stated at the “4 Degrees and Beyond” conference at Oxford that “political reality must be grounded in physical reality or it is completely useless”.

The Sierra Club is experiencing what may be a positive change in leadership and to its credit has not adopted the policy of “corporate engagement” described, yet it has failed to truly mobilize its base against the dangerous shortcomings of the USCAP endorsed legislation. In 2008, the Sierra Club bestowed its highest honor – the John Muir Award – to climate scientist Dr. James Hansen. In presenting the award, Sierra Club President Allison Chin said: “He is truly a hero for preserving the environment”. How does the Sierra Club reconcile the honoring of this man for warning the world and then essentially ignore his core message that present climate legislation is based on false solutions that will waste precious time?

NRDC and EDF, on the other hand, have gone far beyond mere silence. While their websites claim a dedication to public service ( NRDC’s motto is “The Earth’s Best Defense”), they have been actively promoting the USCAP accomodation. If they had not lost sight of their original missions, they would have sought out members of Congress willing to stand up to the fossil fuel industry and used their resources (in 2008, NRDC had an operational budget of 87 million dollars) to throw weight behind them. Instead of emboldening this kind of voice, they have done the exact opposite by allowing industry to define what is “feasible”.

The real climate movement – the one with its backbone intact and composed of grassroots activists and principled groups like Friends of the Earth and Center for Biological Diversity – is already in a “David versus Goliath” situation as it tries to confront the most powerful lobby in the country. But that task has been made infinitely more difficult by these big budget groups using their money to isolate and “box in” the smaller ones.

We close this commentary with the following direct appeal to both the leadership and the members of these groups that have chosen the path of accommodation:

The verdict is in. Your experiment in “corporate engagement” has resulted in a disastrous failure that now threatens the planet. We fully expected the massive campaign from the fossil fuel industry to strip any substance from this legislation. But you have blindsided those of us who are fighting with all our hearts for the future of the earth. Your coffers have grown and now you are using this money to drown us out.

Your stance does not represent those in the grassroots movement, many of whom are young and see the disasters that are looming within their own lifetimes. In your comfortable offices, you do not speak for those willing to put themselves on the line and engage in nonviolent civil disobedience against the very forces you seek to accomodate. The rationale for your corporate “partnerships” was the issue of exerting influence. But the question begging to be asked is who influenced whom? Though your treasury is more full, what truly has been gained and what has been lost?

Your intentions may have been honorable, but the agenda of “defending earth” has been hijacked. Along the way, your vision became blurred and you lost sight of this mission. In this “experiment’, you are the ones who have been “had”. It now appears to have been a terrible Faustian bargain, and we are all paying the price. At the very moment of greatest need for an empowered public advocacy in the face of the most overwhelming threat in human history, your leadership is not to be found.

Your accommodation and your defense of abominably weak Congressional legislation has already had a destructive global impact. It was this legislation that set the bar intolerably low in Copenhagen and instigated a “race to the bottom”. The entire world-wide movement for climate sanity has become blocked by the denial, blindness, and paralysis embodied in U.S. climate policy. When you take this stance in the name of “defending the earth”, you are actually creating an insidious and dangerous deception.

For the sake of the planet, we appeal to your organizations to reclaim the integrity of your original visions. The position you presently advocate will squander the precious little time we have to implement true reductions before the irreversible tipping points are crossed. The stakes could not be higher. We ask that you join hands with the grassroots activists and groups and support the following eight points:

1) Officially recognize that we are truly in a global emergency and that irreversible tipping points are likely to be crossed if humanity does not act in time;

2) Officially recognize that this emergency is of such a magnitude that a war time level of mobilization is needed in order to effectively deal with it;

3) Stand squarely for the necessity that climate legislation be based on the setting of emission reduction targets and a time frame which are defined by the science;

4) Due to the severe ecosystem damage that will ensue in response to a 2 degree (celsius) rise, an overall goal of no more than one degree (celsius) rise must be sought;

5) Clearly renounce cap and trade and offsets as false solutions that will squander precious time;

6) Stand squarely against any attempt in Congress to strip EPA of its authority to regulate carbon;

7) Support a comprehensive approach to the crisis that combines elements of legislation, regulation, and public investment;

8) Support a legislative component based on a continually rising carbon fee with a 100% distribution of the proceeds to U.S. citizens, with the amount of the fee determined by an emission reduction schedule driven by science.

We also ask the members of these groups to withhold their organizational support until their leadership recognizes the necessity of these changes. On this defining issue of our time, may we strive to remove the barriers that divide us and work together.

Gary Houser is a public interest writer, documentary producer, and activist with Climate SOS seeking to raise awareness within the religious community (here) about the moral issues at stake and working to create a more empowered climate movement.

Cory Morningstar, in addition to being a mom, is an activist with Canadians for Action on Climate Change and has collated latest scientific findings here.

The rainforest in the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, Bolivia. Photograph: Pablo Corral Vega/Corbis

The rainforest in the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park, Bolivia. Photograph: Pablo Corral Vega/Corbis

Delegates at the global climate summit failed to figure out a way to stop the destruction of the world’s forests. But some lawmakers think they have a solution, and it relies on financing from some of America’s biggest polluters. Michael Montgomery reports in collaboration with Mark Schapiro.

Delegates at the global climate summit failed to figure out a way to stop the destruction of the world’s forests. But some lawmakers think they have a solution, and it relies on financing from some of America’s biggest polluters. Michael Montgomery reports in collaboration with Mark Schapiro. Several years ago three U.S. companies sank millions of dollars into a forest reserve in southern Brazil to earn credits to cover some of their carbon emissions back in America. How does the scheme work on the ground? Michael Montgomery reports in collaboration with Mark Schapiro.

Several years ago three U.S. companies sank millions of dollars into a forest reserve in southern Brazil to earn credits to cover some of their carbon emissions back in America. How does the scheme work on the ground? Michael Montgomery reports in collaboration with Mark Schapiro.

A green police trooper rides a boat in Brazil.

A green police trooper rides a boat in Brazil. Guarani tribal leader Leonardo Wera Tupa

Guarani tribal leader Leonardo Wera Tupa