May 09

20192

Social Engineering, Whiteness & Aversive Racism

Better Climate’ Commodification of Nature ecosystems as goods and services Extinction Rebellion Green New Deal Greta Thunberg Natural Capital New Climate Economy offsetting losses of biodiversity ‘Better Growth

The Climate Movement: What Next?

Clive L. Spash: Social, Ecological Economics

May 2019

By Clive L. Spash

Joan Wong illustration for Foreign Policy [Source: Why Growth Can’t Be Green]

*Invited Comment for the Tellus Foundation [Note: This short commentary was written as a contribution to a Great Transition (Tellus Institute)roundtable discussion focused on the climate movement that started with an invited statement from Bill McKibben. The focus was on three questions: What is the climate movement’s state of play? System change, not climate change? Do we need a meta-movement?]

A CAPTURED ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENT?

The climate movement, like all environmental NGOs, has been subject to the influence of neoliberalism and corporate capture. Neo-liberals love to attack government while totally ignoring the corporate control of the economy. In the USA the extent of government capture is just ignored (from the President down and not just the most recent President either). There is a general failure to link the social and economic to the ecological. Political analysis is lacking, social theory is absent and there are a dearth of substantive ideas as to alternative economies from the existing paradigms of economic growth and price-making markets.Hence the climate movement promotes price incentives (taxes, carbon trading), innovation and new technologies, commodification of Nature (ecosystems as goods and services, natural capital), offsetting losses of biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions, and new quantitative measures of growth as progress.

TECHNO-OPTIMIST CAPITALISM, GREEN GROWTH AND GREEN NEW DEALS

Cutting past the personal anecdotes, Bill McKibben’s GT piece appears to promote systemic change, but does it really? The piece includes the following:

• “the divestment movement […] with commitments from endowments and other portfolios worth about $8 trillion”

• “Seventy-five years from now, we will run the world on sun and wind because they’re free.” [unlike coal, gas and oil?]

• “we can’t make change happen fast enough”

• “student Climate Strikes now underway thanks to the inspiration of Sweden’s Greta Thunberg”

• “the incredibly exciting fight for a Green New Deal”

• “If we replace fossil fuels with sun and wind, the effect will inevitably lead to at least some erosion of the current power structure.”

• “There will be solar billionaires”

• “The extremely rapid fall in the price of renewable energy and electric storage is one indication that the necessary conditions for rapid change are now in place.”

The aim is for a large shift in financing towards new energy sources, which is basically the mainstream (neoclassical) economic argument that substitutes exist and the price mechanism will supply them. This relies on the belief that price mechanisms send the right signals and actually reflect resource costs rather than being determined by power relations, rules and regulations, subsidies and public infrastructure. If its cheap it must be good. There is little or no connection to politics, resource extractivism or biophysical limits (e.g., on the resources required for electric technologies), nor the need for demand control rather than supply increase. Technology will save us, markets work and there will be ‘free’ electricity for all.

The mythical innovative capitalist entrepreneur of neo-Austrian economics and neoliberal ideology appears to be lurking in the background of such claims. The Green New Deal is similar, subject to being hi-jacked by the entrepreneurial ‘billionaires’. In the USA special rules are proposed to take the trillions outside political process to be placed into the hands of a ‘special committee’, and you can expect the standard vested interests behind the scenes. The French regulation school describe how capitalism has historically adapted in response to the crises it creates; enabling with changes in the controlling minority but maintaining a power bloc that rules over the majority. Karl Polanyi, long ago, noted the way in which crises leads to social payback (e.g., ‘new deals’) to prevent total breakdown, civil unrest and potential rebellion. When that fails it uses authoritarian force, as seen with securitisation and the rise of the political right.

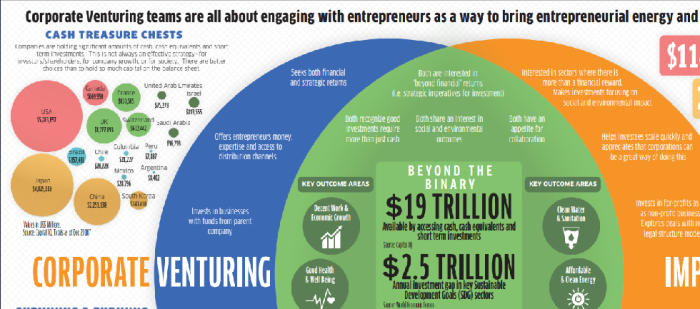

Contrary to McKibben’s claim, there is nothing in the ‘new technologies’ that inevitably changes the political and economic power relationships. Indeed, the trillions being requested are for investment in the growth of the economy via increased ‘green’ industrial energy and market product supply. What stops the money going to the B-Team (that Hans Baer mentions)? Where are the new institutions to prevent funds being funnelled through the usual financial channels and into the hands of the existing power players? Technology does not create institutions, it requires them!

The existing institutions of modern economies are those supporting economic growth. The growth priority has been made clear by the over 3500 economists supporting a climate tax and opposing structural change. Similarly, Lord Stern is the academic figure head of the New Climate Economy, a concept created by members of the Davos elite, with its ‘Better Growth, Better Climate’ reports. Their explicitly stated concern is that: “In the long term, if climate change is not tackled, growth itself will be at risk.” Change is coming and the corporations and billionaires are fully aware of this. They have been actively lobbying on climate and environment since Johannesburg (Earth Summit 2002) and were a dominant force at Paris. They have also long been seeking to control the environmental movement for their own ends.

The ‘smart’ money already supports Extinction Rebellion and Greta Thunberg. Greta is lauded and praised, hosted by the international and Davos elite, and they hope can be used to help spring the trillions of funding. She can expect prizes and awards, as long as she plays the game. Ask yourself how a child is suddenly propelled into the international media limelight and given access to the most powerful people on the planet, and then ask yourself why? Why was she not just ignored like all the protesters saying exactly the same things for decades?

Clearly, as a new superstar environmentalist, a single person, she is useful to circumvent other organisations; useful as long as she attacks the right people (e.g. politicians, ‘government’) as the wrong doers (diverting attention from corporations), and supports funding of the ‘New Economy’ based on innovation, technology, new markets and economic growth. Media can downplay and cut anything critical of the system and the growth economy and report only what serves financial interests. If she turns ‘political’, expect her to be dropped like a hot potato.

Extinction Rebellion (XR) is similarly useful. It claims no political agenda, which is obviously a disingenuous, if not fraudulent, claim. They are engaged in a power struggle, but on whose behalf? Pushing a ‘climate emergency’ that seeks trillions for whom and under what political process of allocation? Claiming the need for a ‘civic forum’, but representative of whom and to endorse what? The honest concern and sincerity of individuals joining XR does not have to be questioned any more than that of Greta. However, there are clearly political games going on here of which its members appear almost willfully ignorant. Who is Extinction Rebellion opposing and where is their political analysis of the power structure that needs to change? What exactly is the change they are seeking? Rebelling against extinction not corporate and state capitalism!?

What is happening right now appears to be a classic case of a passive revolution. When hegemonic power is threatened it captures the movement leaders and neutralises them by bringing them into the power circles and takes the initiative away from radical revolutionary change. In addition, the aim is to split movements and their demands by separating the pragmatic from the radical, forming new alliances with the pragmatic wings and thereby incorporating radical movement language with their own ‘pragmatic’ demands. The threatened elites create captured movements and leaders, adopting the language of the rebels and claiming to address their concerns. Those joining them can claim to be more ‘pragmatic’ because they are connected to the powerful and see how to save the system. None of this is any different from the decades of NGO capture and new environmental pragmatism, but the latest moves are more overt because the stakes are getting higher.

WHAT NEXT?

The climate movement runs along a knife edge between re-establishing another phase of competitive economic growth, and making radical economic and political reform a reality through social ecological transformation. The current thrust is to the former and will remain so as long as the potential forces for change operate via corporations and remain committed to productivism, equitable materialism and nationalism. The climate movement is a real threat to powerful elites and that is exactly why it is being infiltrated and invited to have ‘a seat at the table’. Climate change has been and is being used to wipe off the agenda all other environmental issues and to impose singular ‘solutions’ to systemic problems.

Any ENGO, like any economists, that claims to be free of politics is either totally naïve or totally untrustworthy, and possibly both. Can the Green New Deal be made into a degrowth/post-growth deal which is not controlled by an elite? Can the well-meaning environmentalists campaigning for neoliberal solutions, and going to prison for the wrong reasons, be educated about corporate manipulation and political power?

Activism and academia need to be integrated far more. Solidarity could start with seeking some common understanding of the structure of the political and economic system. Connecting that understanding to biophysical reality also means deconstructing the growth economy not re-establishing it as ‘Green’ based on mythical free energy sources and the benevolence of billionaires.

Yours,

Clive L. Spash

6th May, 2019, Vienna

[Clive L. Spash is an ecological economist. He currently holds the Chair of Public Policy and Governance at Vienna University of Economics and Business, appointed in 2010. He is also Editor-in-Chief of the academic journal Environmental Values. He has been working on climate change as an economist since the late 80s and engage on environmental issues since 70s. His personal website is https://www.clivespash.org/]