Apr 05

20170

Humanitarian Agencies, TckTckTck, USAID, Whiteness & Aversive Racism

8 Miles Fund Absolute Return for Kids (ARK) Africa AIDS Band Aid Imperialism Band Aid/Live Aid Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Bob Geldof Bono CARE Catholic Relief Services Celebrity DATA (Debt David Jones (Havas & Facebook) Ethiopia J.P. Morgan Jeffrey Sachs Maurice Strong Mo Ibrahim Mo Ibrahim Foundation ONE One Young World Save the Children Soros Tck Tck Tck The Politics of Starvation Trade USAID

Bob Geldof and the Aid Industry: “Do They Know it’s Imperialism?”

Under the Mask of Philanthropy

March 29, 2017

by Michael Barker

[Author Michael Barker published the following article in the activist journal Capitalism Nature Socialism in 2014 (Volume 24, No.1, pp.96-110).]

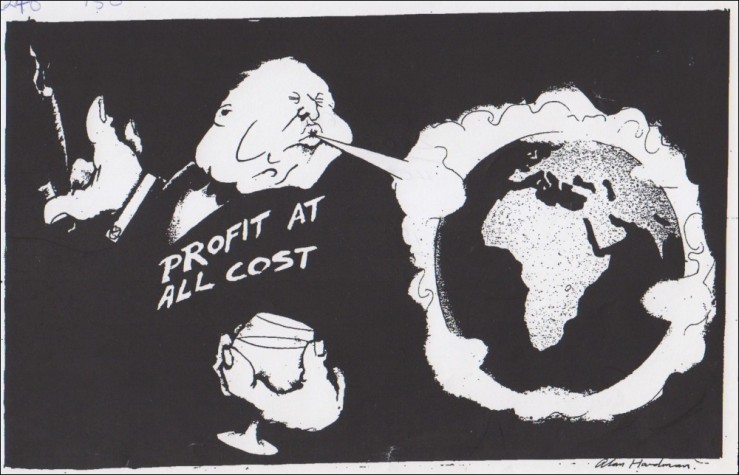

The central role that celebrities maintain within global society provides a good illustration of the essentially hollow and manipulative nature of contemporary democracies. Corporate elites literally manufacture all-star celebrities, and acting through these malleable figureheads, freely flood the world with imperialist propaganda. Much like the economic forces acting to misguide politicians, institutional pressures ensure that only right-thinking individuals become trusted celebrities. However, the main difference between celebrities and politicians is that the public cannot exert democratic control over celebrities. Bob Geldof is no different in this regard, and as the consummate celebrity-power broker, he stands clear of many contemporaries as a pioneer of celebrity-led imperialism: acting effectively in the service of capital. It is for this reason that this article critically excavates such a largely overlooked history to help unearth an explanatory framework for understanding exactly why the ongoing tragedy of famines will never be solved under a capitalist framework.Geldof first rose to fame in the 1970s as the lead singer of the Irish band the Boomtown Rats and, having learned how to play the music industry’s game to perfection, went on to become a rare beneficiary of the stifling culture industry. However, that was not enough for Geldof, and at the peak of his musical career he attempted to give something back to the world; call it something akin to musical social responsibility. For Geldof, this time of charitable maturation arrived in 1984 when, having been shocked by a news report about the ongoing famine in Ethiopia, he sought to harness his celebrity power and to direct it toward the challenge of solving global injustice. Such good intentions are all well and good, but seeing that Geldof explicitly set upon this task in a manner that ignored any systematic critique of the politics of exploitation, his actions ending up bolstering the very same unjust capitalist system that created the problem in the first place. In fact, a good case can be made that it is precisely the imperialism-lite of ostensibly good-intentioned liberal elites—whose activities are subsumed under the kind-sounding rhetoric of “philanthropy,” “democracy,” and “human rights”—that has facilitated the institutionalization of neoliberalism.

Celebrities and the Politics of Starvation

In our interconnected world, extended famines do not occur when harvests fail, or because there are too many mouths to feed; quite the opposite, they occur with unfortunate regularity precisely because geopolitical priorities place profit before people. Scrutinizing the case study provided by the Ethiopian famine is important, as not only did it mark Washington’s “first hundred-million dollar commitment to international disaster relief,” but the intervention has also provided a “blueprint for future policymakers to follow”. Thus, to advance a realistic and useful solution to starvation, one needs to look beyond the mainstream media’s propaganda of futility, and strive to examine the role of capital in catalyzing “natural” disasters. Celebrity activists cannot be relied upon in searching for such solutions; as embedded within capitalist networks of power, they tend to be amongst those few individuals least likely to engage in such a rational approach to problem solving.

Counter to the rational nature of anti-capitalist thought, the latest tried and (media) tested method of addressing capital’s wrong-doings is to harness the angry voice of a celebrity (or better still a group of celebrities) to rant and rave about individual greed. Illustrating this is the latest iteration of a longstanding trend that has seen capitalists harness the power of philanthropy to the extension and consolidation of capitalist relations worldwide. This smokescreen approach to social change channels public attention away from any discussion of meaningful issues, and ensures that capitalists are empowered to “solve” the very same problems they caused in the first place. Geldof is singled out in particular because he took this basic formula for corporate success and then pushed this model for celebrity-led reaction to such an extent that celebrities are now a vital part of the “aid” industry.

Geldof clearly does not interpret his own actions in such a negative way, and seems to believe that the moral suasion of celebrities can force the hands of the very same political and economic elites that sustain their careers. There may be a limited grain of truth in this way of thinking, but it is to state the obvious that a celebrity campaign to expose capitalist injustice is hardly likely to be instigated by corporate-sanctioned celebrities, let alone gain active elite support in corporate circles. Hence, a good case can be made that Geldof’s entire Band Aid/Live Aid phenomenon actually shifted:

… the focus of responsibility for the impoverishment of the Third World from western governments to individuals and obscured the workings of multinational corporations and their agents, the IMF and the World Bank. Worse, it made people in the West feel that famine and hunger were endemic to the Third World, to Africa in particular (the dark side of the affluent psyche), and what they gave was as of their bounty, not as some small for what was taken from the of the Third recompense being poor World…. [A] discourse on western imperialism was transmogrified into a discourse on western humanism. [1]

Geldof’s own humanitarian campaign thus exemplified itself as a stereotypical attack on governments and the existing aid industry: the visual problem was identified (famine), blame was then squarely placed on the local (foreign) government, and a “new” uncorrupted form of charity was then promoted. Along with such myths, he also pushed the equally misleading idea that foreign governments allowed the famine to continue because they were apathetic. Geldof’s serviceable response to these “problems” was obvious; he had to force Western governments to care more for distant others and rail against the existing aid industry’s inefficiencies. In both instances, this meant that Geldof dismissed the primary institutional reason for the existence of the aid industry. This is because governments do not donate food out of generosity; rather their food distribution networks are considered to be an integral weapon through which they promote their foreign policies. Critical books that Geldof might have read at the time include Nicole Ball’s World Hunger: A Guide to the Economic and Political Dimensions (1981), Susan George’s How the Other Half Dies: The Real Reasons for World Hunger (1976), Teresa Hayter’s The Creation of World Poverty (1981), and Marcus Linear’s Zapping the Third World: The Disaster of Development Aid (1985).

Paradoxically, writing in 1986, Geldof was evidently aware (at the rhetorical level anyway) of the strategic use of aid:

Aid is given in direct proportion to how friendly a government is towards the donor. It is used as threat, blackmail and a carrot. This is wrong …. Aid by and large benefits the donor country as much as the recipient, more so in fact as it stimulates, by trade, the donor’s economy, but leaves the recipient aid-dependent. (Bob Geldof, Is That It?, Sidgwick & Jackson, 1986, p.318.)

However, such critical words never informed his actions.

Band Aid Imperialism

Considering the exploitative nature of government food aid, the actions of the glut of “Bloody Do-Gooders” that Geldof brought together under the remit of Band Aid in 1984 certainly need to be viewed in a critical light. [2] Released in December 1984, Band Aid’s humanitarian anthem “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” quickly became the fastest-selling UK single of all time and marked Geldof’s return to the public stage as a born-again humanitarian rabble-rouser. Reflecting on his initial experiences in his autobiography Is That It? (1986), Geldof acknowledged that the result of Band Aid’s fund raising “would be so small in the context of the problem that it would be like putting a tiny plaster on a wound that required twelve stitches” (p.223).

With the benefit of hindsight, I would suggest that this is an extremely bad misdiagnosis. A more accurate description of Band Aid’s work would be to say that they put a plaster over capitalism’s body politics and sutured the public’s eyes shut. Here, Geldof would vehemently disagree as he insists that Band Aid carried out its work without involving itself in regional politics. Such claims, however, are patently false, especially given the fact that he recruited some of Britain’s leading elites to serve as trustees of the charity, the Band Aid Trust, which was set up to distribute the funds raised in the course of his activism. [3]

So how did it all start? If one returns to the initial seven-minute BBC story broadcast on October 24, 1984 that fueled Geldof’s humanitarian impulses, it turns out that the two reporters who filed the report (Mo Amin and Michael Buerk) were working under the auspices of World Vision—a well-publicized, imperialist, evangelical Christian charity. World Vision exists as just one, often overlooked part of imperial counterinsurgency efforts carried out by conservative evangelists who wage “spiritual warfare” upon recalcitrant populations. Little wonder that the television report described Ethiopia as the scene of a “biblical famine,” which was the “closest thing to hell on earth”. Thus, it is appropriate that in the early stages of Geldof’s frantic organizing efforts, the head of World Vision UK, Peter Searle, “kept phoning” Geldof in a bid to influence his activities. Having never heard of World Vision, Geldof recalled that he was “very suspicious” of Searle’s offers of help, but he seems to have been reassured when told that “they were an excellent organization but with roots in the right-wing American evangelical revival.” As Geldof continues: “Later we backed several of their projects” (p.235), [4] but to be more precise, it should be noted that as reported in May 1986, the “largest sum spent so far [by Band Aid] on a single project, dollars 1m, went to the charity World Vision” for their work in the Sudan (“The Band’s Last Big Number/The Future of Band Aid.” The Sunday Times, May 11, 1986).

Lest one forgets, the Cold War was in full swing, and Ethiopia was in the grip of a protracted civil war against rebels of the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). Geldof thankfully recognized the existence of this war; but when he met the officials of the Ethiopian government’s relief commission, he told them, “It seems to me that your basic problem is one of PR.” He added that while “I may not know anything about famine … I do know a lot about PR.” The narrow solution as viewed through Geldof’s celebrity eyes was that Ethiopia should see the international media as their natural ally because, he continued, “once people in the West appreciate the scale of what is going on here you won’t be able to stop them from helping” (p.249). Geldof’s naivety certainly did not make him receptive to the contrary idea presented by members of the Ethiopian government, that the Western media were part of the problem, and that it had actually consciously acted against the best interests of their country. Further, given Geldof’s gross ignorance about Ethiopian politics, it is no surprise that he missed the fact that the Ethiopian government was deliberately withholding food aid from the “huge areas of Tigray where TPLF guerrillas held sway” because, as their acting foreign minister Tibebu Bekele made clear at the time, “Food is a major element in our strategy against the secessionists”. [5]

One might note that the only aid group active in Ethiopia at the time that challenged the hegemonic imperialist discourse of the famine was Médecins sans frontiers, and for doing so, they were promptly ejected from the country. At that time, the longstanding trend of manipulating humanitarian aid to serve the donor countries’ geostrategic interests is most clearly demonstrated in the provision of aid on the borders of Pakistan-Afghanistan and Honduras-Nicaragua during the 1980s. In the former case, Fiona Terry concludes, “Whether they believed they were neutral or not, NGOs that received US funding either in Pakistan or for cross-border operations were assisting the foreign policy strategy of the US government.” With respect to Honduran “aid,” some NGOs themselves were openly critical about such manipulations, and a report by Catholic Relief Services concluded, “The border relief programs are not designed to meet the long- or short-term interests of the Miskitos, but rather are designed for political purposes as a conduit of aid to the contras”. Interestingly in Ethiopia, Catholic Relief Services appear to have maintained a somewhat antagonistic stance vis-à-vis their role in promoting US foreign policy objectives but, despite rhetorical objections, still retained their prestigious position as the largest recipient of US disaster grants.

It is, therefore, far from surprising that more recent reports demonstrate that some of the relief monies entering Ethiopia were used to buy arms for the rebels via the TPLF’s aid front group, the Relief Society of Tigray (REST). The US government was of course well aware of this situation as a now-declassified Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) report written in 1985 makes clear. The report observes, “Some funds that insurgent organizations are raising for relief operations, as a result of increased world publicity, are almost certainly being diverted for military purposes”. Geldof, no doubt dismissed such possibilities as belonging to the realm of conspiracy theories, which is perhaps the reason he did not refuse an offer of aid from the shadowy employee of a former CIA agent. As Geldof recounts in his autobiography, the influential CIA agent in question was Miles Copeland, whose philanthropic-minded boss was the longtime Saudi arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi, and whose militaristic background remained unmentioned by Geldof. Thus, Geldof adds, he was informed by Miles Copeland’s son, Stewart Copeland (the drummer in the rock group The Police), that:

Khashoggi was interested in donating some planes for us to use. On the eve of my departure for Ethiopia I met up with Khashoggi’s son who was passing through London. The planes would be for famine relief in the Sudan only, he said, and a meeting would be arranged between me and President Numeiri’s personal adviser, Baha Idris. It all seemed very complex, but the offer for the planes was firm, I was assured. (p.251) [6]

Then, while on his subsequent foray to the Sudan, Geldof had lunch with Andrew Timpson of Save the Children where his briefing provided:

… one enlightening piece of information. Adnan Khashoggi was said to have oil interests in the Sudan and a special relationship with President Numeiri which led him to getting a remarkably good return on his investment. It was said that if anyone could arrange a cease-fire in the civil war which was disrupting development in the oil field which was thought to be the biggest in black Africa, it was he. (p.252)

Geldof’s follow-up sentence is increasingly curious, but as far as he is concerned, that is the end of the story as he fails to return to this intriguing subject. He does, however, mention in passing that during the preparations for the Band Aid concert, “all the Band Aid office expenses were being paid for by a Malaysian oil millionaire called Ananda Krishnan” and, contrary to Geldof’s own personal intentions for the project, Krishnan “was interested in turning Band Aid into a permanent institution” (p.266). Such curious humanitarian contacts befit a man with little enthusiasm for challenging the legitimacy of powerful political interests. In Geldof’s own words:

[A]s in England, where I didn’t want to get involved in party politics, so too in Africa. ‘I will shake hands with the devil on my left and the devil on my right to get to the people who need help,’ I would say, when I first asked questions about the political complexion of some local government. That was crucial, for you could become bogged down in the myriad moral uncertainties of dealing with an imperfect political system. (p.318)

Geldof Versus the American Government?

Despite Geldof recognizing the fact that aid is regularly used by powerful governments “as threat, blackmail and a carrot,” in 1985, Band Aid strangely sought to gain the support of the best-organized imperialist aid agency in the world, the US Agency for International Development (AID). No need to worry about such incongruous behavior though, as Geldof would have us believe “the greatest single donor in the world” did not really know what it was doing in terms of coordinating its global operations. Geldof recalls that he “was frightened” that USAID “would have the better of me or have a better grasp of the facts.” “But they didn’t” he continues, “we were all tap dancing” (p.320). [7] This seems most peculiar, and I would argue that this interpretation of events owes more to his naivety than to reality, but either way this false impression certainly gave Geldof the confidence boost he needed to argue for their help. That said, he didn’t have to argue much, as USAID already knew his plans, as he “had stipulated the agenda before” he arrived in America. He recalled, “They knew that we were not prepared to leave without firm undertakings from them that they should match us on a dollar-for-dollar basis on some of our mutually beneficial projects” (p.322). So in the end, it is not surprising that the US State Department came through for Band Aid. The Ethiopian government, on the other hand, was, as Geldof reports, “not delirious to have help from US Aid” (p.323).

Are we really to believe that it was Band Aid that manipulated the US government and not vice versa? If we just consider the quantitative issue of food aid, the total value of US aid for Ethiopia in fiscal 1983 was around $3 million; this then increased to some $23 million the following year, and then “jumped to more than four times that amount (about $98 million) between October 1 and December 1, 1984.” Given that approximately two-thirds of this last increase was committed after the initial National Broadcasting Company (NBC) broadcast of the famine in the United States (October 24, 1984), one way of interpreting this change would be to say this boost in aid was due to the change in media coverage and the resulting public outcry. Alternatively, one could just as easily interpret this change as illustrating that the media became more receptive to the issue once the US government signaled that they were increasing, and no longer decreasing, food aid to the region. This latter argument is evidenced by the fact that in March 1984, Senator John Danforth (Republican-Missouri)—who throughout 1984 played an important role in lobbying for famine relief in Ethiopia —successfully introduced a bill (H.J.Res. 493) that provided $90 million in food assistance for emergency food assistance for Africa. This money was not, however, freed up until an earlier bill (H.J.Res. 492), which aimed to provide $150 million to famine-stricken areas in Africa (which the $90 million represented part of) stalled, passing into law in July 1984, but only when proposed amendments to add covert funding for the Contras in Nicaragua had been dropped from the bill (African Famine: Chronology of U.S. Congressional and Executive Branch Action in 1984, Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service).

Counter to Geldof’s recommendation to Ethiopian officials that they only needed better PR to get their story out to the global public, US journalists had been attempting to air stories about the famine for some time, but they simply had no takers in the mainstream media. As far as the media were concerned, “It was not ‘new’ news, for the roots of the 1984 disaster lay in conditions known for years before the disaster hit the headlines”. However, by the end of the year, Ethiopia was now considered as being an issue that deserved political attention. One wondered if this was in any way related to ongoing attempts to coerce the Ethiopian government to accept more aid from the West. For example, it is interesting to observe that just after the increase in aid and media attention (in October), Reuters reported on December 1, 1984, how “The Marxist Government of Ethiopia has agreed to move toward a free market policy to improve the country’s agricultural production…” (“Ethiopians Consider Free Market.” The Globe and Mail, December 1, 1984). Thus, extensive economic and diplomatic pressure was clearly being brought to bear on Ethiopia well before the rise in media attention. By way of another example, the Italian government had its own important role to play in ramping up the political pressure, “and the Italian ambassador is generally credited with making it clear to Mengistu in early October 1984 that Ethiopia could not continue to suppress information about the famine, but must publicize it in order to attract Western relief”.

Ethiopia was now the media’s number one story, but during the seemingly endless deluge of one-dimensional coverage, at no point did the mainstream media help the public understand what was happening by making any significant effort to explain the root causes of the famine. One would have been hard-pressed to have heard of the ambitious land reform program—launched in 1975 when the military Marxists (known as the Derg) rose to power—that was “very successful in eliminating large holdings, absentee landlordism and landlessness.” Similarly, there was no talk of how the Derg’s top-down control over their agrarian reform program had the net effect of “lessen[ing] farmer’s incentives for good natural resource management by decreasing both the security of land tenure and the profitability of agriculture”. Factors that combined with the prolonged civil war and the Derg’s massive resettlement program (which was undertaken in the wake of the 1984–1985 famine) exacerbated farmer land insecurity and mismanagement, which depressed agricultural production in Ethiopia’s time of need.

Instead of providing historically-informed investigative journalism that explored such issues, the racist media delivered up a nightmarish story about a natural disaster of biblical proportions. This is an outcome that was entirely predictable given the propagandist nature of the mainstream media that was well aligned to celebrate the successes of the imperialist development narratives upon which the nongovernmental (NGO) aid industry operates. Thus, the media and the international aid community simply latched onto well-worn neo-Malthusian environmental degradation narratives to justify ongoing aid in the post-famine period (1985–1990). Likewise, little or no mention has been made of the deleterious effect that the Soviet Union’s policy of disengagement had on the nominally Marxist government.

Such an ill-informed development narrative was supremely useful to imperialist donors as it promoted an intervention in a geostrategically important region which “was narrowly technical, largely bypassed the Ethiopian government, was targeted directly on the rural poor and would be welcomed by the growing environmental lobby in Washington”. With respect to the utility of this massive influx of aid (for the people of Ethiopia), “in retrospect, it is clear that much of this effort was wasted or counterproductive.” It is not coincidental that it was during this golden period of “development” aid that the Derg “moved away from socialist agriculture”.

One might point out that neo-Malthusian arguments drawn upon in Ethiopia are intimately enmeshed with the ideological underpinnings of the mainstream environmental movement, which are especially in line with the environmental lobby in Washington. Indeed, since the 18th century, such specious logic has solidified yeomen service to imperial elites who falsely argue that humans simply cannot cultivate enough food to feed the entire human population. Thus, given Ethiopia’s positioning in the ongoing Cold War, it is appropriate that the leading proponents of neoliberal environmentalism played a major role in justifying the aid communities’ protracted interventions in the region. For example, from late 1984 to mid-1986, the executive coordinator of the United Nations Office for Emergency Operations in Africa was none other than , the immensely powerful former oil executive who, over the past four decades, has arguably done more than any other individual to promote the misnomer of sustainable development.

Capitalists for Just Exploitation

Old humanitarian habits die hard and, having already proved their ability to neglect the role of imperial power politics in global affairs, Geldof and his Band Aid friends have continued to act as willing implementers of capitalistic responses to capitalist-bred inequality. However, if one had to choose one Band Aid contributor who best followed Geldof’s own model of leadership on behalf of imperial elites it would have to be Bono, who in 2005 was voted TIME magazine’s Person of the Year alongside the well-known “humanitarian” couple Bill and Melinda Gates. After contributing to the Band Aid single and the Live Aid gig in 1985, Bono had even emulated Geldof’s commitment to the right-wing evangelical charity World Vision, and spent six weeks volunteering at one of their orphanages in Ethiopia. Bono’s overt commitment to Christian missionary work was then put on hold, that is, until 1997 when Jamie Drummond encouraged him to became a spokesperson for a church-based campaign known as Jubilee 2000, a group which was set up to campaign the canceling of Third World debt. Fresh from this spiritual revival, Bono then began spending weekends at the World Bank with his friend Bobby Shriver, who himself was an old colleague of the World Bank’s president, James Wolfensohn, having worked with him within the venture capital division of the Wolfensohn Firm.

Having gained his humanitarian apprenticeship under leading imperialists like Wolfensohn, it is fitting that economist Jeffrey Sachs completed Bono’s education. Bono, like Geldof, was pioneering new ground within the realm of celebrity activism, moving from the former archetypal celebrity-as-fundraiser to the realm of celebrity-as-corporate-lobbyist. With the zeal of a born-again zealot, Bono endeavored to work the circuits of power of the hallowed nonprofit-industrial complex, and in 2002 he turned to Geldof, who helped devise the name DATA (Debt, AIDS, Trade, Africa) to christen his and Bobby Shriver’s new group; this organization flourished with $1 million start-up grants flowing in from the likes of global democracy manipulator George Soros, software businessman Edward W. Scott, Jr., and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Once established, DATA recruited like-minded high profile corporate lobbyists, the two main ones being the Democrat AIDS activist /defense contractor lobbyist Tom Sheridan, and Scott Hatch, who formerly ran the National Republican Campaign Committee. Much like Geldof, Bono sees his work as bipartisan, that is, encompassing all political views as long as they stand firmly on the side of capitalism.

In 2004, Bono extended his activist commitments, and with the backing of Bread for the World, the Better Safer World coalition, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation he created “ONE: The Campaign to Make Poverty History,” which merged with DATA in 2007 and is now known as ONE Campaign. All board members of ONE are leading representatives of the US power elite, but three who exhibit outstanding service to capitalist propaganda are president and CEO Michael Elliott (who most recently served as the editor of TIME International), board chair Tom Freston (who is the former CEO of Viacom and MTV Networks), and Joe Cerrell (who presently works for the Gates Foundation, but formerly served as the vice president of the philanthropy practice at APCO Worldwide and as assistant press secretary to former US Vice President Al Gore). A significant recent addition to ONE’s board of directors is World Bank Managing Director Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, who is active on the board of Friends Africa where he sits alongside African “friends” like Jeffrey Sachs and the chairman of De Beers, Jonathan Oppenheimer. Yet another especially interesting ONE board member is Helene Gayle, who as a former employee of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is now employed as the president of the leading international “aid” outfit, CARE.

Here, it is noteworthy to recall that CARE was formed by Herbert Hoover as the Cooperative for American Remittances to Europe, and since its inception in 1945 has provided a valuable means of promoting imperialism via the strategic provision of food aid. Indeed, as Susan George suggests in her excellent book How the Other Half Dies: The Real Reasons for World Hunger (1976), Hoover was given the opportunity to form CARE primarily because he had demonstrated his ability to use food aid as a weapon during and after World War I. In fact, she suggests that Hoover was arguably the “first modern politician to look upon food as a frequently more effective means of getting one’s own way than gunboat diplomacy or military intervention”. As recent critical scholarship on the international role of CARE demonstrates, it still serves much the same imperial purpose that it was created to perform.

CARE thus provides a vital training ground for budding “humanitarians”; for instance, many of their former staff are involved in a relatively new venture known as Build Africa—a “charity” working in rural Uganda and Kenya that helps “young people” better themselves through learning about the wonders of “business enterprise.” One particularly significant trustee of Build Africa (who also heads their board of ambassadors/investment bankers) is the investment banker and private equity power broker Mark Florman, the CEO of the British Venture Capital Association. In addition to acting as one of the co-founders of the UK-based Center for Social Justice—a think tank that was set up in 2004 by the former leader of the Conservative party, Iain Duncan Smith [8]—Florman worked with Bob Geldof to raise $200 million to launch a private equity fund in 2012, called 8 Miles, with the aid of , which, bluntly put, aims to capitalize on Africa. According to the Financial Times:

Among others that Mr. Geldof has approached for advice on the [] venture is Mo Ibrahim, the Sudanese-born telecoms tycoon turned philanthropist, and Arki Busson, the founder of hedge fund EIM. He has also discussed his plans with Tony Blair, the former British prime minister who sits with Mr. Geldof on the Africa Progress Panel, monitoring donor commitments towards increased aid to Africa. [9]

To flesh out the backgrounds of Geldof’s new friends, one might note that Mo Ibrahim was soon to be a board member of the ONE Campaign and is currently chair of the advisory board for an investment firm focused on Africa called Satya Capital; its small portfolio includes Namakwa Diamonds, a mining group whose board members notably include a former executive vice president of the notorious Barrick Gold. In 2004, Ibrahim founded the Mo Ibrahim Foundation “to recognize achievement in African leadership and stimulate debate on good governance across sub-Saharan Africa and the world.” In this context, “good governance” means implementation of neoliberal reforms. [10] Hedge fund tycoon Arki Busson, like Ibrahim, is well-versed in the power of philanthropic propaganda, and on the side of his main business interests he runs an educational charity known as Absolute Return for Kids (ARK), which is one of Britain’s powerful new academy chains that run academies on US charter school lines. In 2007, at ARK’s seventh annual fundraiser, Geldof and Tony Blair were in attendance, so it is suitable that ARK’s patrons include two close associates of Geldof’s. The first is the “human rights” crooner Sir Elton John, and the second is the former World Bank economist Dambisa Moyo.

Moyo is the author of Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa (2009), and she lividly expresses her humanitarian commitment through service on the boards of Barclays, SABMiller PLC, and the global independent oil and gas exploration and production company, Lundin Petroleum. [11] With “her total unflinching faith in markets as the ultimate solution and her silence on issues of social justice” Moyo’s book sits comfortably with the ambitions of the “Bono-Bob Geldof-driven development industry that is convinced that the ingredients of lifting the wretched of the earth out of poverty include higher economic growth, liberalised markets, good governance, better-funded NGOs and, most important of all, more aid”.

A Leftist critic of the aid industry (and of Geldof in particular) reminds us:

[t]o understand the Geldof phenomenon, we need to look historically at the role that Africa has played in the European imagination and in global capitalism. Geldof’s crusade and attitude is not new. He is only the latest in a long line of European men whose personal mission has been to transform Africa and Africans. David Livingstone, the celebrity of his day, embarked on a similar crusade in the late 19th century, painting Africa as a land of “evil,” of hopelessness and of child-like humans. His mission was to raise money to pursue his personal ambitions.

In this manner, “Livingstone’s and Geldof’s humanitarianism fits well with the demands of global capitalism as they serve to obscure distinct phases in the exploitation of Africa.

Close Your Minds and Give Your Money!

Contrary to the pleasant-sounding rhetoric accompanying the entire Band Aid phenomena, Band Aid and its offshoots have always worked closely with imperialist policy agendas. Thus, the Band Aid Trust still exists, with the most recent revival of their formula for deception being the Live8 concert, which was held in 2005, which again relied heavily upon the two most famous celebrity big hitters, Geldof and Bono. While Geldof and Bono’s initial approach to humanitarianism could at best be described as naïve, the power-struck duo are now quite obviously working hand-in-hand with neoliberal elites, not in solidarity with the poor and oppressed. So while the musicians involved in the first Band Aid project might argue that they were unaware of the means by which food aid is tied to imperialism, the same could be not true of the artists who participated in the monumental corporate aid bonanza that was Live8. After all, it was there that Geldof introduced Bill Gates to the millions watching Live8 as “the world’s greatest philanthropist”; George Monbiot appropriately observed, “Geldof and Bono’s campaign for philanthropy portrays the enemies of the poor as their saviours.”

Over the past three decades, the formidable Bono-Geldof tag-team has provided a vital propaganda service to ruling elites. On a broader level too, some argue that their celebrity activism is a natural corollary to the politics of privatization. C. Wright Mills, in his seminal book, The Power Elite (1953), dedicated an entire chapter to celebrities, observing that with the rise of national means of mass communication, “the institutional elite must now compete with and borrow prestige from these professionals in the world of the celebrity.” He thereby outlined the integral function that celebrity lives fulfill vis-à-vis the requirements of managing democracy, noting “the liberal rhetoric—as a cloak for actual power—and the professional celebrity—as a status distraction—do permit the power elite conveniently to keep out of the limelight”. Writing so many years ago, Mills was unsure as to whether the power elite would be content to rest uncelebrated; however, now, under neoliberal regimes of media and social management, the differences between interests of the jet setting crowd and other parts of the power elite have converged. Celebrities become political leaders and politicians become world class “actors,” while the real power behind these media-friendly figureheads remains in the hands of an increasingly concentrated economic elite.

Notes

1 For a musical critique of Live Aid see Chumbawamba’s album Pictures of Starving Children Sell Records: Starvation, Charity and Rock & Roll – Lies & Traditions (1986).

2 Geldof’s initial suggestion for Band Aid’s name was “The Bloody Do-Gooders.”

3 Geldof was also involved in the US version of Band Aid which under the organization of Harry Belafonte released the song “We Are the World” in March 1985, which became the fastest-selling American pop single in history. The Band Aid Trust was initially chaired by Lord Gowrie, then Minister for the Arts. Other founding trustees included Lord Harlech, the head of Harlech TV, Michael Grade, the controller of BBC1, Chris Morrison, the manager of Ultravox, Maurice Obserstein, the chairman of the British Phonographic Institute, John Kennedy, a pop industry lawyer, and Midge Ure (Geldof 1986 Geldof, B. 1986. Is That It? London: Sidgwick & Jackson. [Google Scholar], 256).

4 On his first visit to Ethiopia, Geldof bumped into another conservative religious “aid” worker, Mother Teresa (Geldof, Is That It? p.239), who according to Christopher Hitchens “has consoled and supported the rich and powerful, allowing them all manner of indulgence, while preaching obedience and resignation to the poor.”

5 One should look to Ethiopia’s recent past for similar examples that illustrate the political nature of famines. For example, “During the final two years (1973–1975) of the US-supported Haile Selassie regime, some 100,000 Ethiopians died of starvation due to drought. At least half the amount of grain needed to keep those people alive was held in commercial storage facilities within the country. In addition, Emperor Selassie’s National Grain Corporation itself held in storage 17,000 tons of Australian wheat which it refused to distribute. While commercial interests thrived by selling hundreds of tons of Ethiopian grain, beans, and even milk to Western Europe and Saudi Arabia, the Ethiopian government received 150,000 tons of free food from aid donors”.

6 Khashoggi was the arms dealer in the Iran-Contra scandal.

7 “The impact of food aid can only be understood within the context of the broader US aid programme. Two-thirds of the total aid package is security assistance: military aid and cash transfers to governments deemed ‘strategically important’ to the US national interest. So whatever worthwhile may be achieved by feeding some people or supporting some useful development efforts is far outweighed by the propping up of anti-democratic elites and regimes whose policies perpetuate inequality”.

8 It is interesting to note that the Executive Director of the Centre for Social Justice, Philippa Stroud, was recently employed by the charity known as Christian Action Research and Education, which is also known as CARE, and whose activities are separate from the aforementioned “aid” agency with the same acronym. The long-serving chair of Christian Action Research and Education is Lyndon Bowring, who is a council member of the conservative Christian group The Evangelical Alliance and a member of the board of reference of the equally zealous Christian Solidarity Worldwide that is very active in promoting “aid” in the Sudan.

9 The “core funding 2008–2010” for the Africa Progress Panel “comes from two sources: the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID).” Africa Progress Panel, available online at: http://www.africaprogresspanel.org/en/about/, accessed 11 January, 2012.

10 Mo Ibrahim is one of many elite counselors of a group called One Young World, which describes itself as “the premier global forum for young people of leadership calibre.” Bob Geldof is also counted as one of their counselors, and One Young World’s cofounder, marketing executive David Jones boasts of “work[ing] closely” with David Cameron and the Conservative Party in the UK and having been tasked to “create and lead the Tck Tck Tck, Time for Climate Justice Campaign.” For an insightful critique of this latter campaign, see Cory Morningstar’s “Eyes Wide Shut: TckTckTck Expose from Activist Insider.”

11 Lukas Lundin a board member of Lundin Petroleum serves as the chair of Lundin Mining, a corporation whose CEO, Phil Wright, is the former president of Freeport-McMoran’s Tenke Mining.

August 28, 2014

by Maximilian Forte

The following is an extract from my chapter, “Imperial Abduction Lore and Humanitarian Seduction,” which serves as the introduction to Good Intentions: Norms and Practices of Imperial Humanitarianism (Montreal: Alert Press, 2014), pp. 1-34:

Outsourcing Empire, Privatizing State Functions: NGOs

First, we need to get a sense of the size and scope of the spread of just those NGOs that work on an international plane, or INGOs, many of which are officially associated with, though not part of, the UN. Estimates of the number of INGOs (such as Care, Oxfam, Médecins Sans Frontières) vary greatly depending on the source, the definition of INGOs used, and the methods used to locate and count them. In broad terms, INGOs numbered roughly 28,000 by the mid-1990s, which represented a 500% increase from the 1970s; other estimates suggest that by the early years of this century they numbered 40,000, while some put the number at around 30,000, which is still nearly double the number of INGOs in 1990, and some figures are lower at 20,000 by 2005 (Anheier & Themudo, 2005, p. 106; Bloodgood & Schmitz, 2012, p. 10; Boli, 2006, p. 334; Makoba, 2002, p. 54). While the sources differ in their estimates, all of them agree that there has been a substantial rise in the number of INGOs over the past two decades.

Second, there is also evidence that INGOs and local NGOs are taking on a much larger role in international development assistance than ever before. The UK’s Overseas Development Institute reported in 1996 that, by then, between 10% and 15% of all aid to developing countries was channeled through NGOs, accounting for a total amount of $6 billion US. Other sources report that “about a fifth of all reported official and private aid to developing countries has been provided or managed by NGOs and public-private partnerships” (International Development Association [IDA], 2007, p. 31). It has also been reported that, “from 1970 to 1985 total development aid disbursed by international NGOs increased ten-fold,” while in 1992 INGOs, “channeled over $7.6 billion of aid to developing countries”.1 In 2004, INGOs “employed the full time equivalent of 140,000 staff—probably larger than the total staff of all bilateral and multilateral donors combined—and generated revenues for US$13 billion from philanthropy (36%), government contributions (35%) and fees (29%)” (IDA, 2007, p. 31). The budgets of the larger INGOs “have surpassed those of some Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) donor countries” (Morton, n.d., p. 325). For its part, the US government “gave more than twice the amount of aid assistance in 2000 ($4 billion) through nongovernmental organizations than was given directly to foreign governments (est. $1.9 billion)” (Kinney, 2006, p. 3).

The military is one arm of the imperialist order, and the other arm is made up of NGOs (though often these two arms are interlocked, as even Colin Powell says in the introductory quote in this chapter). The political-economic program of neoliberalism is, as Hanieh (2006, p. 168) argues, the economic logic of the current imperialist drive. This agenda involves, among other policies, cutbacks to state services and social spending by governments in order to open up local economies to private and non-governmental interests. Indeed, the meteoric rise of NGOs, and the great increase in their numbers, came at a particular time in history: “the conservative governments of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher made support for the voluntary sector a central part of their strategies to reduce government social spending” (Salamon, 1994). By more or less direct means, sometimes diffuse and other times well-coordinated, the interests of the US and its allies can thus be pursued under the cover of humanitarian “aid,” “charity,” and “development assistance”.

In his extensive critique of neoliberalism, David Harvey (2005) credits the explosive growth of the NGO sector under neoliberalism with the rise of, “the belief that opposition mobilized outside the state apparatus and within some separate entity called ‘civil society’ is the powerhouse of oppositional politics and social transformation” (p. 78). Yet many of these NGOs are commanded by unelected and elite actors, who are accountable primarily to their chief sources of funds, which may include governments and usually includes corporate donors and private foundations. The broader point of importance is that this rise of NGOs under neoliberalism is also the period in which the concept of “civil society” has become central not just to the formulation of oppositional politics, as Harvey (2005, p. 78) argues, but also central to the modes of covert intervention and destabilization openly adopted by the US around the world. More on this just below, but first we need to pause and focus on this emergence of “civil society” as a topic in the new imperialism.

The “Civil Society” of the New Imperialism: Neoliberal Solutions to Problems Created by Neoliberalism

There has been a growing popularization of “civil society,” that James Ferguson, an anthropologist, even calls a “fad”. Part of the growing popularity of this concept is tied to some social scientists’ attraction to democratization, social movements and NGOs, and even some anthropologists have been inspired to recoup the local under the heading of “civil society” (Ferguson, 2007, p. 383). The very notion of “civil society” comes from 18th-century European liberal thought of the Enlightenment, as something that stood between the state and the family. “Civil society” has been universalized, with “little regard for historical context or critical genealogy”:

Today “civil society” has been reconceived as the road to democratization and freedom, and is explicitly promoted as such by the US State Department. Whether from the western left or right which have both appropriated the concern for “civil society,” Ferguson argues that the concept helps to legitimate a profoundly anti-democratic politics (2007, p. 385).

The African state, once held high as the chief engine of development, is now treated as the enemy of development and nation-building (especially by western elites), constructed as too bureaucratic, stagnant and corrupt. Now “civil society” is celebrated as the hero of liberatory change, and the aim is to get the state to become more aligned with civil society (Ferguson, 2007, p. 387). Not only that, the aim is to standardize state practices, so as to lessen or remove barriers to foreign penetration and to increase predictability of political outcomes and investment decisions (see Obama, 2013/7/1).

In practice, most writers conceive of contemporary “civil society” as composed of small, voluntary, grassroots organizations (which opens the door, conceptually, to the focus on NGOs). As Ferguson notes, civil society is largely made up of international organizations:

That NGOs serve the purpose of privatizing state functions, is also demonstrated by Schuller (2009) with reference to Haiti. NGOs provide legitimacy to neoliberal globalization by filling in the “gaps” in the state’s social services created by structural adjustment programs (Schuller, 2009, p. 85)—a neoliberal solution to a problem first created by neoliberalism itself. Moreover, in providing high-paying jobs to an educated middle class, NGOs serve to reproduce the global inequalities created by, and required by, neoliberal globalization (Schuller, 2009, p. 85). NGOs also work as “buffers between elites and impoverished masses” and can thus erect or reinforce “institutional barriers against local participation and priority setting” (Schuller, 2009, p. 85).

Thanks to neoliberal structural adjustment, INGOs and other international organizations (such as the UN, IMF, and World Bank) are “eroding the power of African states (and usurping their sovereignty),” and are busy making “end runs around these states” by “directly sponsoring their own programs or interventions via NGOs in a wide range of areas” (Ferguson, 2007, p. 391). INGOs and some local NGOs thus also serve the purposes of neoliberal interventionism.

Trojan Horses: NGOs, Human Rights, and Intervention to “Save” the “Needy”

David Harvey argues that “the rise of advocacy groups and NGOs has, like rights discourses more generally, accompanied the neoliberal turn and increased spectacularly since 1980 or so” (2005, p. 177). NGOs have been called forth, and have been abundantly provisioned as we saw above, in a situation where neoliberal programs have forced the withdrawal of the state away from social welfare. As Harvey puts it, “this amounts to privatization by NGO” (2005, p. 177). NGOs function as the Trojan Horses of global neoliberalism. Following Chandler (2002, p. 89), those NGOs that are oriented toward human rights issues and humanitarian assistance find support “in the growing consensus of support for Western involvement in the internal affairs of the developing world since the 1970s”. Moreover, as Horace Campbell explained,

Private military contractors in the US, many of them part of Fortune 500 companies, are indispensable to the US military—and in some cases there are “clear linkages between the ‘development ‘agencies and Wall Street” as perhaps best exemplified by Casals & Associates, Inc., a subsidiary of Dyncorp, a private military contractor that was itself purchased by Cerberus Capital Management for $1.5 billion in 2010, and which received financing commitments from Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Citigroup, Barclays, and Deutsche Bank (Campbell (2014/5/2). Casals declares that its work is about “international development,” “democracy and governance,” and various humanitarian aid initiatives, in over 25 countries, in some instances working in partnership with USAID and the State Department’s Office of Transition Initiatives (Campbell (2014/5/2).

In order for NGOs to intervene and take on a more prominent role, something else is required for their work to be carried out, in addition to gaining visibility, attracting funding and support from powerful institutions, and being well placed to capitalize on the opportunities created by neoliberal structural adjustment. They require a “need” for their work. In other words, to have humanitarian action, one must have a needy subject. As Andria Timmer (2010) explains, NGOs overemphasize poverty and stories of discrimination, in order to construct a “needy subject”—a population constructed as a “problem” in need of a “solution”. The needs identified by NGOs may not correspond to the actual needs of the people in question, but need, nonetheless, is the dominant discourse by which those people come to be defined as a “humanitarian project”. To attract funding, and to gain visibility by claiming that its work is necessary, a NGO must have “tales that inspire pathos and encourage people to act” (Timmer, 2010, p. 268). However, in constantly producing images of poverty, despair, hopelessness, and helplessness, NGOs reinforce “an Orientialist dialectic,” especially when these images are loaded with markers of ethnic otherness (Timmer, 2010, p. 269). Entire peoples then come to be known through their poverty, particularly by audiences in the global North who only see particular peoples “through the lens of aid and need” (Timmer, 2010, p. 269). In the process what is also (re)created is the anthropological myth of the helpless object, one devoid of any agency at all, one cast as a void, as a barely animate object through which we define our special subjecthood. By constructing the needy as the effectively empty, we thus monopolize not only agency but we also corner the market on “humanity”.

References

Anheier, H. K., & Themudo, N. (2005). The Internationalization of the Nonprofit Sector. In R. D. Herman (Ed.), The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and Management, 2nd ed. (pp. 102–127). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc.

Bloodgood, E., & Schmitz, H. P. (2012). Researching INGOs: Innovations in Data Collection and Methods of Analysis. Paper presented at the International Studies Association Annual Convention, March 31, San Diego, CA.

http://faculty.maxwell.syr.edu/hpschmitz/papers/researchingingos_february6.pdf

Boli, J. (2006). International Nongovernmental Organizations. In W. W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The Nonprofit Sector (pp. 333–351). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Campbell, H. C. (2014/5/2). Understanding the US Policy of Diplomacy, Development, and Defense: The Office of Transition Initiatives and the Subversion of Societies. CounterPunch.

http://www.counterpunch.org/2014/05/02/the-office-of-transition-initiatives-and-the-subversion-of-societies/

Chandler, D. (2002). From Kosovo to Kabul: Human Rights and International Intervention. London, UK: Pluto Press.

Ferguson, J. (2007). Power Topographies. In D. Nugent & J. Vincent (Eds.), A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics (pp. 383–399). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hanieh, A. (2006). Praising Empire: Neoliberalism under Pax Americana. In C. Mooers (Ed.), The New Imperialists: Ideologies of Empire (pp. 167–198). Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications.

Harvey, D. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

International Development Association (IDA). (2007). Aid Architecture: An Overview of the Main Trends in Official Development Assistance Flows. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

http://www.worldbank.org/ida/papers/IDA15_Replenishment/Aidarchitecture.pdf

Kinney, N. T. (2006). The Political Dimensions of Donor Nation Support for Humanitarian INGOs. Paper presented at the International Society for Third Sector Research (ISTR) Conference, July 11, Bangkok, Thailand.

http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.istr.org/resource/resmgr/working_papers_bangkok/kinney.nancy.pdf

Makoba, J. W. (2002). Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs) and Third World Development: An Alternative Approach to Development. Journal of Third World Studies, 19(1), 53–63.

Morton, B. (n.d.). An Overview of International NGOs in Development Cooperation. United Nations Development Program.

http://www.undp.org/content/dam/china/docs/Publications/UNDP-CH11%20An%20Overview%20of%20International%20NGOs%20in%20Development%20Cooperation.pdf

Obama, B. (2013/7/1). Remarks by President Obama at Business Leaders Forum. Washington, DC: The White House, Office of the Press Secretary.

http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/01/remarks-president-obama-business-leaders-forum

Salamon, L. M. (1994). The Rise of the Nonprofit Sector. Foreign Affairs, July-August.

http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/50105/lester-m-salamon/the-rise-of-the-nonprofit-sector

Schuller, M. (2009). Gluing Globalization: NGOs as Intermediaries in Haiti. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 32(1), 84–104.

Timmer, A. D. (2010). Constructing the “Needy Subject”: NGO Discourses of Roma Need. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 33(2), 264–281.

+++

Norms and Practices of Imperial Humanitarianism

Edited by Maximilian C. Forte

Montreal, QC: Alert Press, 2014

Hard Cover ISBN 978-0-9868021-5-7

Paperback ISBN 978-0-9868021-4-0