Unmasking the “Good Intentions” of Canadian NGOs

May 30, 2014

by Fernanda Sánchez Jaramillo

Interview with Nik Barry-Shaw, coauthor, with Dru Oja Jay, of Paved with Good Intentions, Canada´s Development NGOs from Idealism to Imperialism

Fernanda Sánchez Jaramillo: What is the contribution of your book to the understanding of Canadian Foreign Policy?

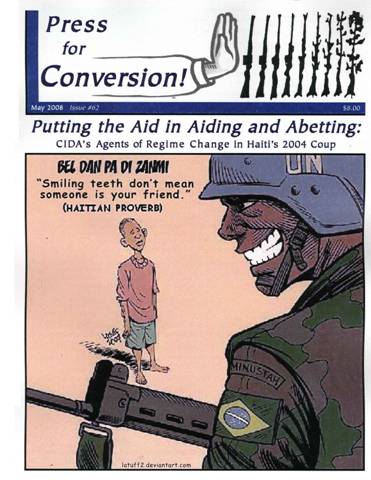

democratically-elected government was what really woke up many people on the left (including Dru and I) to the reality of Canadian imperialism. Several of us involved in Haiti solidarity work began studying the history of Canadian foreign policy, and concluded that Canada was not simply being pushed around by the U.S.; it was an advanced capitalist power that had its own economic interests in the Global South that it sought to advance, through violence if necessary. Left nationalist analyses of Canada as a “rich dependency” under the thumb of the U.S. simply did not do justice to the high levels of initiative and involvement demonstrated by the Canadian state in orchestrating the Haitian coup, and many other instances. So one thing our book is trying to do is to debunk widely-held perceptions of Canada’s foreign policy as that of a uniquely benevolent “peacekeeper” nation.

democratically-elected government was what really woke up many people on the left (including Dru and I) to the reality of Canadian imperialism. Several of us involved in Haiti solidarity work began studying the history of Canadian foreign policy, and concluded that Canada was not simply being pushed around by the U.S.; it was an advanced capitalist power that had its own economic interests in the Global South that it sought to advance, through violence if necessary. Left nationalist analyses of Canada as a “rich dependency” under the thumb of the U.S. simply did not do justice to the high levels of initiative and involvement demonstrated by the Canadian state in orchestrating the Haitian coup, and many other instances. So one thing our book is trying to do is to debunk widely-held perceptions of Canada’s foreign policy as that of a uniquely benevolent “peacekeeper” nation.London, 1st of May 2012: Women of Colour in the Global Women’s Strike campaigners gather outside the British Red Cross offices, to protest alleged theft of money donated for humanitarian relief and of failing to alleviate the suffering of Haitians. Photo P Nutt

Aren´t Canadian NGOs hypocritical in claiming to help rebuild democracy and bring health care in Africa while oppressing First Nations and cutting health care services for Canadian citizens and refugees, including those from Africa? →