Dec 04

20172

Imperialist Wars/Occupations, Whiteness & Aversive Racism

Afghanistan Doctors Without Borders Imperialism Médecins Sans Frontières Misery Industry Social Documentary Unicef

AFGHANISTAN: DOCTORS WITHOUT BORDERS RECOGNIZED AS THE TOP BRAND IN THE MISERY INDUSTRY

Photographer: keith harmon snow

Exhibit Title: His Name was Dilawar

Location: Afghanistan

Exhibit Abstract

“‘Great Harm Has Been Done to US,’ declared George Bush in a speech thunderously applauded by the U.S. Congress on 20 September 2001. With this disingenuous slogan the United States directed its unaccountable permanent warfare machine at the people of Afghanistan, a place that few U.S. citizens know much about. Our ‘allies’ jumped aboard, unleashing high-tech weaponry and shock-and-awe destruction on a simple people that have been subject to the nasty prerogatives of Empire since ~ 1838.

Civilians bear the brunt of this ugly war: over the past 4 years far more than 33,000 Afghan civilians were injured or killed. The cowardice of our war includes drone strikes, targeted assassinations, ‘dirty tricks’ black operations, snatch-and-snuff kidnappings, torture—all as policy. The War of Terror has caused millions of direct / indirect deaths since 2001, and millions more displaced persons, and the U.S. has committed war crimes and crimes against humanity.”

Dilawar of Yakubi was a young taxi driver tortured/killed by U.S. troops in Afghanistan.

+++

“Decades of war means destruction of homes and villages, destruction of crops, croplands mined, failed crops, and rising displacement. Starvation and malnutrition were named in a major New York Times ‘news’ article that appears to be more a plug for the UNICEF brand and the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières brand than any serious reportage on the hunger crisis. The disingenuous title of the January 2014 article was: ‘Afghanistan’s Worsening, and Baffling, Hunger Crisis.’ What is baffling? This is a way to diminish responsibility and deflect attention from the obvious causes of starvation, crop failures, starvation, malnutrition, high infant mortality, and other obvious effects of the illegal U.S. war in Afghanistan. Further, the article notes that ‘despite years of Western involvement and billions of dollars in humanitarian aid to Afghanistan, children’s health is not only still a problem, but also worsening’ but nowhere does the New York Times probe the massive corruption and outright (advertising & branding) lies of the for-profit humanitarian sector that, obviously, benefits from our permanent warfare economy.”

“Hunger in Afghanistan is a very real problem. These children play at sunset amidst piles of grain being processed—separating the wheat from the chaff using straw brooms on a dirt ground—by their fathers and uncles. To grasp the gross inequity between the level of suffering for children in Afghanistan (the target population that the AID industry preys upon), consider that combined salaries of the top seven Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières executives total $1,169,715 (* 2016 IRS form 990) and they receive $256479 in ‘other’ compensation. Of course, information about Doctors Without Borders/Medecins Sans Frontieres corporate sponsors is not easily discoverable from either their web site or their published reports available therein.”

“This father and his son suffer alike after the child was wounded and rests in critical condition in a hospital bed in Kabul.”

“The landscapes in Afghanistan are vast, and the real reasons for the war are for access to the land and its natural resources. In the calculated equations of predatory western capitalism and the profit motives of unconscious demagogues and warmongers the people of Afghanistan are considered in the way: they are expendable, and the depopulation of Afghanistan is underway.”

“Afghan herders often trip unexploded ordnance and land mines while herding domestic donkeys, sheep and goats. Landmines and other battlefield unexploded ordnance (UXOs) contaminate at least 724 million square meters of land in Afghanistan, more than any other country in the world. Only two of Afghanistan’s twenty-nine provinces are believed to be free of landmines. The Northern Alliance and United Front forces have laid mines, while many Russian-era mines remain. According to Human Rights Watch in 2001, the Taliban had stopped using landmines in 1998, declaring it un-Islamic and punishable by death; after 1998 the Taliban were often falsely blamed for using them. Mine clearance teams in Afghanistan still find UXOs from the former Soviet Union but also from Belgium, Italy, the United States and Britain. The United States dropped about 1,228 cluster bombs containing 248,056 bomblets between October 2001 and March 2002 alone; these weapons destroyed the homes and lives of countless civilians.”

“Afghan men discuss war and politics outside a mosque in northern Afghanistan. The people are angry at the U.S. occupation, the corruption of their leaders working with the occupation, and they admit that every U.S. attack redoubles the popular resistance to the U.S. and its goals.”

“Afghan farmers see the profit and value in planting their fields in poppies. The Central Intelligence Agency and U.S. military have their fingers in the Afghan opium/heroin trade: heroin processed in Afghanistan by ‘Taliban’ and ‘Isis’ and other factions backed by the U.S. does not leave Afghanistan on the backs of donkeys. Warlords run the heroin business. The heroin is allegedly shipped by air to Bondsteel Air Base in Kosovo, where it is then allegedly distributed to Western Europe by the Albanian mafia.”

“As Dr. Alfred McCoy pointed out: On 16 November 2017 the United Nations released its opium report for 2017: total crop area up from 200,000 hectares in 2016 to 328,000 hectares in 2017; the opium harvest nearly doubled since 2016 from 4,600 to 9,000 tons, well above the 2007 peak of 8,200 tons.”

“A boy of ten years old—another obvious civilian casualty in the U.S.-led war “to win hearts and minds”—rests awake and immobile and terrified, his wounds still fresh and bloody, in the intensive care section of a hospital in Kabul.”

“The LOVE THY ENEMY sign I posted on my family’s farmland in Williamsburg Massachusetts on September 13, 2001, defaced over night by local people directly connected to the war machine. The people responsible for the war in suffering in Afghanistan and Iraq and Syria and Central Africa are the people of the western nations whose soldiers are fighting and killing there, the populations whose complacency and acceptance make these wars in ‘far off places’ possible. There is little discussion of these wars in popular quarters in the United States, Canada or Europe, as they are hidden and downplayed and obfuscated by the western media propaganda system. The U.S. population is deeply divided between those who favor war and killing and ‘putting America first’ at all costs, and those who see the pointlessness of war, and the profits being made to sustain it, at the expense of all people everywhere, and at the expense of nature, and all of planet earth.”

View Keith Harmon Snow’s stunning exhibition, in it’s entirety:

http://socialdocumentary.net/exhibit/keith_harmon_snow

[Keith Harmon Snow has worked as a journalist, war correspondent, genocide investigator and/or photographer in 46 countries — often traveling by simple means (mountain bike, raft, horse, foot) to enable a deeper engagement with the land and people. He is the 2009 Regent’s Lecturer in Law & Society at the University of California, Santa Barbara, recognized for over a decade of work documenting war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. He is also a certified Holotropic Breathwork facilitator, and author of the non-fiction book: The Worst Interests of the Child: The Trafficking of Children & Families Through U.S. Family Courts. In July 2016 his SDN exhibit Inside the Company, Down on the Farm (plantations in the DR Congo) won an Honorable Mention in the SDN Call for Entries on The Fine Art of Documentary. He is available for assignment. You can also visit his website All Things Pass.]

August 28, 2014

by Maximilian Forte

The following is an extract from my chapter, “Imperial Abduction Lore and Humanitarian Seduction,” which serves as the introduction to Good Intentions: Norms and Practices of Imperial Humanitarianism (Montreal: Alert Press, 2014), pp. 1-34:

Outsourcing Empire, Privatizing State Functions: NGOs

First, we need to get a sense of the size and scope of the spread of just those NGOs that work on an international plane, or INGOs, many of which are officially associated with, though not part of, the UN. Estimates of the number of INGOs (such as Care, Oxfam, Médecins Sans Frontières) vary greatly depending on the source, the definition of INGOs used, and the methods used to locate and count them. In broad terms, INGOs numbered roughly 28,000 by the mid-1990s, which represented a 500% increase from the 1970s; other estimates suggest that by the early years of this century they numbered 40,000, while some put the number at around 30,000, which is still nearly double the number of INGOs in 1990, and some figures are lower at 20,000 by 2005 (Anheier & Themudo, 2005, p. 106; Bloodgood & Schmitz, 2012, p. 10; Boli, 2006, p. 334; Makoba, 2002, p. 54). While the sources differ in their estimates, all of them agree that there has been a substantial rise in the number of INGOs over the past two decades.

Second, there is also evidence that INGOs and local NGOs are taking on a much larger role in international development assistance than ever before. The UK’s Overseas Development Institute reported in 1996 that, by then, between 10% and 15% of all aid to developing countries was channeled through NGOs, accounting for a total amount of $6 billion US. Other sources report that “about a fifth of all reported official and private aid to developing countries has been provided or managed by NGOs and public-private partnerships” (International Development Association [IDA], 2007, p. 31). It has also been reported that, “from 1970 to 1985 total development aid disbursed by international NGOs increased ten-fold,” while in 1992 INGOs, “channeled over $7.6 billion of aid to developing countries”.1 In 2004, INGOs “employed the full time equivalent of 140,000 staff—probably larger than the total staff of all bilateral and multilateral donors combined—and generated revenues for US$13 billion from philanthropy (36%), government contributions (35%) and fees (29%)” (IDA, 2007, p. 31). The budgets of the larger INGOs “have surpassed those of some Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) donor countries” (Morton, n.d., p. 325). For its part, the US government “gave more than twice the amount of aid assistance in 2000 ($4 billion) through nongovernmental organizations than was given directly to foreign governments (est. $1.9 billion)” (Kinney, 2006, p. 3).

The military is one arm of the imperialist order, and the other arm is made up of NGOs (though often these two arms are interlocked, as even Colin Powell says in the introductory quote in this chapter). The political-economic program of neoliberalism is, as Hanieh (2006, p. 168) argues, the economic logic of the current imperialist drive. This agenda involves, among other policies, cutbacks to state services and social spending by governments in order to open up local economies to private and non-governmental interests. Indeed, the meteoric rise of NGOs, and the great increase in their numbers, came at a particular time in history: “the conservative governments of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher made support for the voluntary sector a central part of their strategies to reduce government social spending” (Salamon, 1994). By more or less direct means, sometimes diffuse and other times well-coordinated, the interests of the US and its allies can thus be pursued under the cover of humanitarian “aid,” “charity,” and “development assistance”.

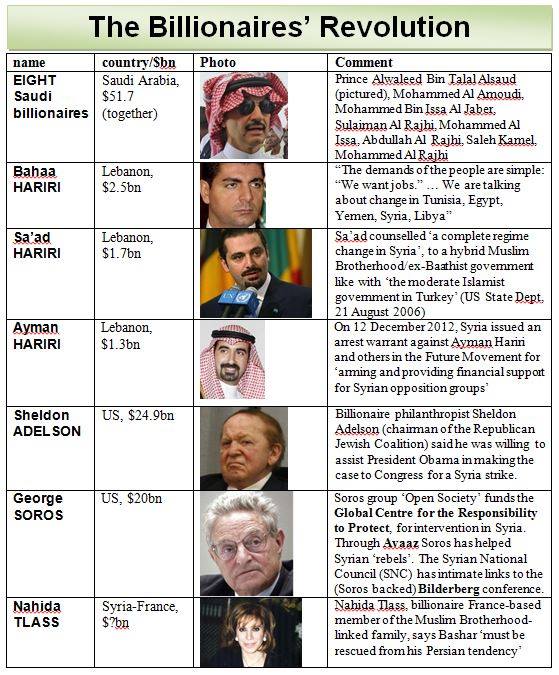

In his extensive critique of neoliberalism, David Harvey (2005) credits the explosive growth of the NGO sector under neoliberalism with the rise of, “the belief that opposition mobilized outside the state apparatus and within some separate entity called ‘civil society’ is the powerhouse of oppositional politics and social transformation” (p. 78). Yet many of these NGOs are commanded by unelected and elite actors, who are accountable primarily to their chief sources of funds, which may include governments and usually includes corporate donors and private foundations. The broader point of importance is that this rise of NGOs under neoliberalism is also the period in which the concept of “civil society” has become central not just to the formulation of oppositional politics, as Harvey (2005, p. 78) argues, but also central to the modes of covert intervention and destabilization openly adopted by the US around the world. More on this just below, but first we need to pause and focus on this emergence of “civil society” as a topic in the new imperialism.

The “Civil Society” of the New Imperialism: Neoliberal Solutions to Problems Created by Neoliberalism

There has been a growing popularization of “civil society,” that James Ferguson, an anthropologist, even calls a “fad”. Part of the growing popularity of this concept is tied to some social scientists’ attraction to democratization, social movements and NGOs, and even some anthropologists have been inspired to recoup the local under the heading of “civil society” (Ferguson, 2007, p. 383). The very notion of “civil society” comes from 18th-century European liberal thought of the Enlightenment, as something that stood between the state and the family. “Civil society” has been universalized, with “little regard for historical context or critical genealogy”:

Today “civil society” has been reconceived as the road to democratization and freedom, and is explicitly promoted as such by the US State Department. Whether from the western left or right which have both appropriated the concern for “civil society,” Ferguson argues that the concept helps to legitimate a profoundly anti-democratic politics (2007, p. 385).

The African state, once held high as the chief engine of development, is now treated as the enemy of development and nation-building (especially by western elites), constructed as too bureaucratic, stagnant and corrupt. Now “civil society” is celebrated as the hero of liberatory change, and the aim is to get the state to become more aligned with civil society (Ferguson, 2007, p. 387). Not only that, the aim is to standardize state practices, so as to lessen or remove barriers to foreign penetration and to increase predictability of political outcomes and investment decisions (see Obama, 2013/7/1).

In practice, most writers conceive of contemporary “civil society” as composed of small, voluntary, grassroots organizations (which opens the door, conceptually, to the focus on NGOs). As Ferguson notes, civil society is largely made up of international organizations:

That NGOs serve the purpose of privatizing state functions, is also demonstrated by Schuller (2009) with reference to Haiti. NGOs provide legitimacy to neoliberal globalization by filling in the “gaps” in the state’s social services created by structural adjustment programs (Schuller, 2009, p. 85)—a neoliberal solution to a problem first created by neoliberalism itself. Moreover, in providing high-paying jobs to an educated middle class, NGOs serve to reproduce the global inequalities created by, and required by, neoliberal globalization (Schuller, 2009, p. 85). NGOs also work as “buffers between elites and impoverished masses” and can thus erect or reinforce “institutional barriers against local participation and priority setting” (Schuller, 2009, p. 85).

Thanks to neoliberal structural adjustment, INGOs and other international organizations (such as the UN, IMF, and World Bank) are “eroding the power of African states (and usurping their sovereignty),” and are busy making “end runs around these states” by “directly sponsoring their own programs or interventions via NGOs in a wide range of areas” (Ferguson, 2007, p. 391). INGOs and some local NGOs thus also serve the purposes of neoliberal interventionism.

Trojan Horses: NGOs, Human Rights, and Intervention to “Save” the “Needy”

David Harvey argues that “the rise of advocacy groups and NGOs has, like rights discourses more generally, accompanied the neoliberal turn and increased spectacularly since 1980 or so” (2005, p. 177). NGOs have been called forth, and have been abundantly provisioned as we saw above, in a situation where neoliberal programs have forced the withdrawal of the state away from social welfare. As Harvey puts it, “this amounts to privatization by NGO” (2005, p. 177). NGOs function as the Trojan Horses of global neoliberalism. Following Chandler (2002, p. 89), those NGOs that are oriented toward human rights issues and humanitarian assistance find support “in the growing consensus of support for Western involvement in the internal affairs of the developing world since the 1970s”. Moreover, as Horace Campbell explained,

Private military contractors in the US, many of them part of Fortune 500 companies, are indispensable to the US military—and in some cases there are “clear linkages between the ‘development ‘agencies and Wall Street” as perhaps best exemplified by Casals & Associates, Inc., a subsidiary of Dyncorp, a private military contractor that was itself purchased by Cerberus Capital Management for $1.5 billion in 2010, and which received financing commitments from Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Citigroup, Barclays, and Deutsche Bank (Campbell (2014/5/2). Casals declares that its work is about “international development,” “democracy and governance,” and various humanitarian aid initiatives, in over 25 countries, in some instances working in partnership with USAID and the State Department’s Office of Transition Initiatives (Campbell (2014/5/2).

In order for NGOs to intervene and take on a more prominent role, something else is required for their work to be carried out, in addition to gaining visibility, attracting funding and support from powerful institutions, and being well placed to capitalize on the opportunities created by neoliberal structural adjustment. They require a “need” for their work. In other words, to have humanitarian action, one must have a needy subject. As Andria Timmer (2010) explains, NGOs overemphasize poverty and stories of discrimination, in order to construct a “needy subject”—a population constructed as a “problem” in need of a “solution”. The needs identified by NGOs may not correspond to the actual needs of the people in question, but need, nonetheless, is the dominant discourse by which those people come to be defined as a “humanitarian project”. To attract funding, and to gain visibility by claiming that its work is necessary, a NGO must have “tales that inspire pathos and encourage people to act” (Timmer, 2010, p. 268). However, in constantly producing images of poverty, despair, hopelessness, and helplessness, NGOs reinforce “an Orientialist dialectic,” especially when these images are loaded with markers of ethnic otherness (Timmer, 2010, p. 269). Entire peoples then come to be known through their poverty, particularly by audiences in the global North who only see particular peoples “through the lens of aid and need” (Timmer, 2010, p. 269). In the process what is also (re)created is the anthropological myth of the helpless object, one devoid of any agency at all, one cast as a void, as a barely animate object through which we define our special subjecthood. By constructing the needy as the effectively empty, we thus monopolize not only agency but we also corner the market on “humanity”.

References

Anheier, H. K., & Themudo, N. (2005). The Internationalization of the Nonprofit Sector. In R. D. Herman (Ed.), The Jossey-Bass Handbook of Nonprofit Leadership and Management, 2nd ed. (pp. 102–127). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc.

Bloodgood, E., & Schmitz, H. P. (2012). Researching INGOs: Innovations in Data Collection and Methods of Analysis. Paper presented at the International Studies Association Annual Convention, March 31, San Diego, CA.

http://faculty.maxwell.syr.edu/hpschmitz/papers/researchingingos_february6.pdf

Boli, J. (2006). International Nongovernmental Organizations. In W. W. Powell & R. Steinberg (Eds.), The Nonprofit Sector (pp. 333–351). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Campbell, H. C. (2014/5/2). Understanding the US Policy of Diplomacy, Development, and Defense: The Office of Transition Initiatives and the Subversion of Societies. CounterPunch.

http://www.counterpunch.org/2014/05/02/the-office-of-transition-initiatives-and-the-subversion-of-societies/

Chandler, D. (2002). From Kosovo to Kabul: Human Rights and International Intervention. London, UK: Pluto Press.

Ferguson, J. (2007). Power Topographies. In D. Nugent & J. Vincent (Eds.), A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics (pp. 383–399). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hanieh, A. (2006). Praising Empire: Neoliberalism under Pax Americana. In C. Mooers (Ed.), The New Imperialists: Ideologies of Empire (pp. 167–198). Oxford, UK: Oneworld Publications.

Harvey, D. (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

International Development Association (IDA). (2007). Aid Architecture: An Overview of the Main Trends in Official Development Assistance Flows. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

http://www.worldbank.org/ida/papers/IDA15_Replenishment/Aidarchitecture.pdf

Kinney, N. T. (2006). The Political Dimensions of Donor Nation Support for Humanitarian INGOs. Paper presented at the International Society for Third Sector Research (ISTR) Conference, July 11, Bangkok, Thailand.

http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.istr.org/resource/resmgr/working_papers_bangkok/kinney.nancy.pdf

Makoba, J. W. (2002). Nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs) and Third World Development: An Alternative Approach to Development. Journal of Third World Studies, 19(1), 53–63.

Morton, B. (n.d.). An Overview of International NGOs in Development Cooperation. United Nations Development Program.

http://www.undp.org/content/dam/china/docs/Publications/UNDP-CH11%20An%20Overview%20of%20International%20NGOs%20in%20Development%20Cooperation.pdf

Obama, B. (2013/7/1). Remarks by President Obama at Business Leaders Forum. Washington, DC: The White House, Office of the Press Secretary.

http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/01/remarks-president-obama-business-leaders-forum

Salamon, L. M. (1994). The Rise of the Nonprofit Sector. Foreign Affairs, July-August.

http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/50105/lester-m-salamon/the-rise-of-the-nonprofit-sector

Schuller, M. (2009). Gluing Globalization: NGOs as Intermediaries in Haiti. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 32(1), 84–104.

Timmer, A. D. (2010). Constructing the “Needy Subject”: NGO Discourses of Roma Need. PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 33(2), 264–281.

+++

Norms and Practices of Imperial Humanitarianism

Edited by Maximilian C. Forte

Montreal, QC: Alert Press, 2014

Hard Cover ISBN 978-0-9868021-5-7

Paperback ISBN 978-0-9868021-4-0