Climate and War: Bill McKibben’s Deadly Miscalculation

November 6, 2019

By Luke Orsborne

Source: British Psychological Society

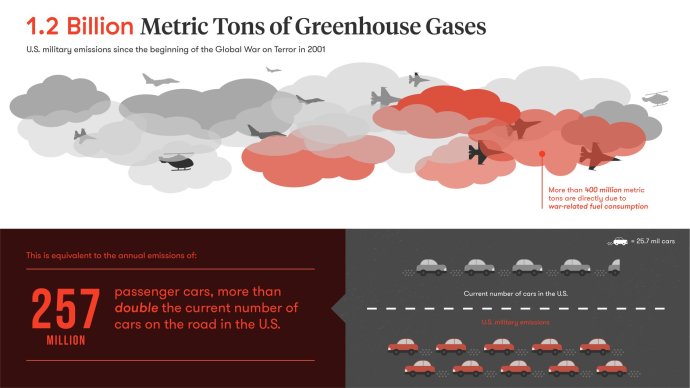

In late June 2019, author and founder of 350.org Bill McKibben produced an article for the New York Review of Books whose headline echoed a growing awareness of the significant role of US militarism in our current ecological crisis. The hook, unfortunately, appeared to be little more than a ruse to entice those who harbor legitimate concerns about the military’s role in the climate crisis in order to then minimize those concerns. What followed was a presentation of selective information, including a superficial critique of US military energy efficiency, that in the end only obfuscates the true cost and context of US militarism as it applies to the health of people and the planet. The result was that rather than highlighting the need for deep structural change which involves putting an end to aggressive US foreign policy, McKibben came across as a cautious cheerleader for the continued centrality of US militarism in global affairs as we enter into an increasingly chaotic, climate destabilized world. This dangerous stance only bolsters the propaganda of so-called “humanitarian interventionism” and a world order built upon violent, neoliberal imperialism.June 12, 2019: “Since the beginning of the post-9/11 wars, the U.S. military has emitted 1.2 BILLION metric tons of greenhouse gases. The Pentagon is the world’s single largest consumer of oil and a top contributor to climate change.” [Source]

McKibben begins his article by admitting that the US Department of Defense is a major consumer of fossil fuels, but then makes the deceptive claim that the “enormous military machine produces about 59 million metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions annually.” Using selective information from a paper entitled Pentagon Fuel Use, Climate Change, and the Costs of War by Professor Neta Crawford of Boston University, a paper which he references heavily for his piece, McKibben goes on to dishonestly downplay the role of the US military in the climate crisis. According to McKibben, this average of 59 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions (which according to Crawford’s paper, the figure between 2001-2017 is actually closer to 70 million) “is not a particularly large share of the world’s, or even our nation’s, energy consumption.” McKibben adds, “Crawford’s careful analysis shows that the Department of Defense consumes roughly a hundred million barrels of oil a year. The world runs through about a hundred million barrels of oil a day. Even though it’s the world’s largest institutional user of energy, the US military accounts, by Crawford’s figures, for barely 1 percent of America’s greenhouse gas emissions.”

In fact, this was not at all the conclusion that Crawford drew from her research. While McKibben mischaracterizes Crawford’s paper as “comprehensive,” Crawford is, by contrast, careful to note that there are in fact several unknowns and unexplored areas when it comes to calculating the fuel use of the military, all of which suggest that the total usage is likely significantly higher than McKibben concludes. She spells out the various sources of military emissions clearly, both those considered and those left unknown, in list form toward the beginning of her paper:

“1. Overall military emissions for installations and non-war operations.

2. War-related emissions by the US military in overseas contingency operations.

3. Emissions caused by US military industry—for instance, for production of weapons and ammunition.

4. Emissions caused by the direct targeting of petroleum, namely the deliberate burning of oil wells and refineries by all parties.

5. Sources of emissions by other belligerents.

6. Energy consumed by reconstruction of damaged and destroyed infrastructure.

7. Emissions from other sources, such as fire suppression and extinguishing chemicals, including Halon, a greenhouse gas, and from explosions and fires due to the destruction of non-petroleum targets in warzones.”

Crawford then clarifies by stating that her focus is “on the first two sources of military GHG emissions—overall military and war-related emissions” and that she will “briefly discuss military industrial emissions.” According to Department of Energy data used in Crawford’s analysis, the total greenhouse gas emissions from the DOD between 2001-2017 was approximately 1.212 billion metric tons. But in the very next section, which McKibben fails to mention, Crawford estimates what the emissions burden of the industrial production of military hardware and munitions might entail. Her calculations are perhaps somewhat rudimentary, but they nonetheless suggest a much greater potential for military produced GHGs than McKibben is willing to admit. If Crawford’s estimates are correct, the combined total of industrial production related emissions and commonly measured military operating emissions would triple the amount of greenhouse gases that are emitted in sustaining our current military infrastructure. Crawford states:

“The estimate above focuses on DOD emissions. Yet, a complete accounting of the total emissions related to war and preparation for it, would include the GHG emissions of the military industry. The military industry directly employs about 14.7 percent of all people in the US manufacturing sector. Assuming that the relative size of direct employment in the domestic US military industry is an indicator for the portion of the military industry in the US industrial economy, the share of US greenhouse gas emissions from the US based military industry is estimated to be about 15 percent of total US industrial greenhouse gas emissions. If half of those military related emissions are attributable to the post-9/11 wars, then US war manufacturing has emitted about 2,600 million megatons of CO2 equivalent greenhouse gas from 2001 to 2017, averaging 153 million metric tons of CO2e each year.”

Furthermore, Crawford goes into more detail in the Appendix as to why the estimates of CO2e impacts are likely understated. Firstly, she notes that the military documents the impact of methane released from fuel consumption as 25 times as potent in its warming potential as compared to CO2, but the IPCC puts this number at 35. In fact, on shorter time scales, scientists have shown that methane is 85 times or more as powerful a greenhouse gas as CO2.

Secondly, she draws attention to the fact that the additives in jet fuel are not accounted for when tabulating the effects of GHG emissions, suggesting significant unknowns. She states that “While the Department of Energy figures and the calculations here include nitrous oxide and methane, it is possible that the additional effects of high altitude water vapor and additives for jet fuel combustion, which are not included in these calculations, may be significant.”

The third point she brings to bear is the lack of inclusion of all the sources of fuel used by the military in their bookkeeping. One of these sources is known as bunker fuel which, as Crawford writes, is excluded from emission accounts as part of the Kyoto Protocol.

Barry Sanders, author of The Green Zone, The Environmental Costs of Militarism, has also written about bunker fuel. Along with this “off the record, ghost stuff,” as he refers to it, Sanders has enumerated various other ways in which the military has been able to underplay its fossil fuel usage. Among these are the unaccounted for fuel used by interdependent contractors in increasingly privatized warzones, and the no cost fuel provided at times by partner nations like Kuwait.

According to the high end of Sanders’ estimates, which do not include the emissions incurred from weapons manufacture, the total percentage of military emissions from the direct burning of fossil fuels may be more like 5 percent of total US emissions. This figure also does not take into consideration other factors touched upon by Crawford, mentioned above, like emissions from ongoing oil fires, which lasted in some cases for months, and the effect of cement production and equipment operation during post war reconstruction, a significant contributor to atmospheric greenhouse gases. Crawford also recognizes that the militaries of all parties drawn into US-led wars have an unaccounted for carbon footprint when honestly examining the total emissions costs of the American war machine.

These additional factors make calculating the true cost of war next to impossible but, in pure greenhouse gas emissions terms, the numbers are clearly significantly higher than what McKibben has suggested. The counter to this conclusion is that even if the military GHG emissions were in the neighborhood of 5 percent of total US emissions (and it’s possibly higher than this), this is still a much smaller number than the rest of the US economy, which is essentially the argument that McKibben has already made. While 5 percent is not an insignificant figure, this line of argument fails to understand the systemic nature of our problem by making the common mistake of focusing narrowly on GHG emissions. It is an entirely reductive and simplistic lens that dangerously distorts, rather than clarifies humanity’s global, interconnected crisis.

Mosaic Solar. Further reading: From Stable to Star – The Making of North American “Climate Heroes”

After completely misrepresenting the calculations found in Crawford’s paper and restricting debate to the evaluation of deflated GHG emissions figures, McKibben takes a further misstep by having us believe that rather than being a hindrance to resolving the climate crisis, the military can actually be a vital asset. While admitting that the military absorbs a massive amount of money each year from American taxpayers, even going so far as to repeat the widely circulated statistic that the US spends as much as the next seven countries combined on its massive defense budget, McKibben seems to believe in some ways this could in fact be a good thing. He suggests that the technologies developed by the military’s R&D could be utilized in the civilian sector, saying that “The military-industrial complex may not be the single best place to conduct R&D, but given current political realities, it is likely to be one of the few places where it’s actually possible.”

In fact, any genuine grassroots movement that is interested in tackling issues as large as the collapse of human civilization and the destruction of global biotic communities would be less interested in acquiescing to “current political realities” which include a $1.25 trillion war budget, and more interested in engendering the kind of struggle needed to define those realities along the lines of an actually livable, equitable future.

The text reads “The Navajo Nation encompasses more than 27,000 square miles across three states – New Mexico, Utah + Arizona – and is the largest home for indigenous people in the U.S.. From 1944 to 1986, hundreds of uranium and milling operations extracted an estimated 400 million tons of uranium ore from Diné (Navajo) lands. [1][Source: jetsonorama: stories from ground zero, August 31, 2019]

Military R&D is not geared toward saving the planet from human destruction. Any overlaps with so-called green technological development is secondary to its primary, narrow framework of creating efficient systems of killing to protect a national agenda set by the interests of the wealthy elite. This framework, more often than not, runs contrary to environmental protection. From the radioactive contamination of people and land caused by the use of depleted uranium, to the pollution of drinking water, to the creation of hundreds of superfund sites across the US, America’s military is well understood to be not just a massive source of greenhouse gases, but one of the largest polluters on the planet.

Furthermore, military R&D is often more about lining the pockets of weapons manufacturers than simply developing an effective end product. Waste and cost overruns are a regular feature in the development of military hardware. The F-35 fighter jet, for example, is expected to cost over a trillion dollars over the course of its sixty year lifespan. In a movement that is looking to maximize efficiency of resource usage, it would clearly make more sense to directly fund efforts to that end, rather than relying on the tangential work of an institution engaging in the most unsustainable activities ever conceived: spending trillions of dollars directly destroying land and infrastructure which is then rebuilt.

What McKibben further fails to acknowledge in his article is that the US military has fostered an atmosphere for intensified global destabilization, international distrust, and environmental degradation at a time when the need for global cooperation and environmental stewardship has never been more clear. Accepting the prioritization of US military spending over the dedication of national resources toward environmental research, habitat restoration, and climate mitigation, as McKibben does, is worse than defeatism. It is ultimately a collusion with the most murderous institution in living memory at the expense of genuine social progress or even human survival. While mainstream environmental groups often shun or disavow direct action that involves property destruction or widespread social disruption used as a tactic to secure the survival of the species, a tactic which is increasingly viewed through the lens of a militarized state as a form of terrorism, these nonprofits often have no qualms about tacitly, or even explicitly, supporting an institution that uses organized mass violence in order to further the very political ends which have brought humanity to the brink of extinction.

November, 2016, Standing Rock: The U.S. Army attempts to evict Oceti Sakowin encampments from treaty lands. Photo by Rob Wilson Photography [Source]

What this translates to is perhaps the most critical point presented in this article, which is that as corporate controlled governments and the officials within them are unable to come to meaningful agreements that could at least slow the process of ecological collapse, Bill McKibben is giving a pass to an institution whose job directly involves sowing violent discord around the world. Military adventurism is part and parcel to a world that is enmeshed in competition for resources, power, and strategic high ground rather than cooperation. To not point this out, and to instead highlight the supposedly positive role that the military will play, represents the betrayal of any vision of a decent future for life on earth under the cover of “current political realities”, which in fact is the reality of collective annihilation. The millions of victims of countless forms of Western imperial aggression stand as a testament to that fact, and the distortions and omissions of Bill McKibben cannot be tolerated by people who stand for justice and a livable future.

And while McKibben praised the military for “doing a not-too-shabby job of driving down its emissions—they’ve dropped 50 percent or so since 1991,” he neglected to mention in his article that it was this hyper competitive culture of US militarism that helped turn up the pressure on negotiators for the 1997 Kyoto Protocol in order to exempt militaries around the world from greenhouse gas accounting. The author of the paper Demilitarization for Deep Decarbonization, Tamara Lorincz, described the successful efforts of government officials, military brass, and oil industry insiders working together to keep military carbon pollution off the ledgers. She quotes lead Kyoto negotiator Stuart Eizenstat, then Under Secretary for Economic, Business, and Agricultural Affairs at a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing:

“We took special pains, working with the Defense Department and with our uniformed military, both before and in Kyoto, to fully protect the unique position of the United States as the world’s only super power with global military responsibilities. We achieved everything they outlined as necessary to protect military operations and our national security. At Kyoto, the parties, for example, took a decision to exempt key overseas military activities from any emissions targets, including exemptions for bunker fuels used in international aviation and maritime transport and from emissions resulting from multilateral operations.”

Rather than standing up for environmental protection, the military, as one would expect, sought to preserve not simply US supremacy, but a global order in which militarism in general continues to play a central role in the affairs of humanity. Fewer regulations are better for weapons manufacturers around the globe, and the US is also the leading weapons exporter on the planet.

In her paper, Lorincz goes on to quote President Clinton appointee, Secretary of Defense William Cohen who said, “We must not sacrifice our national security… to achieve reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.” In 2015, the non-binding Paris Climate Accords put an end to the accounting exemption set forth in Kyoto, but without an enforcement mechanism to ensure compliance, it did not explicitly mandate military reductions, leaving it up to individual nations to address those concerns as they saw fit. The priorities of the nation were further clarified when in 2019, in a paper about the grave danger posed by climate change, published by the US Army War College, the military’s role as protector of a pathological order again came on display. The paper stated, “The U.S. military must immediately begin expanding its capability to operate in the Arctic to defend economic interests and to partner with allies across the region…This rapid climate change will continue to result in increased shipping transiting the Arctic, population shifts to the region and increased competition to extract the vast hydrocarbon resources more readily available as the ice sheets contract. These changes will drive an expansion of security efforts from nations across the region as they vie to claim and protect the economic resources of the region.” There is no call in these words to change the kind of thinking that would have nations fighting over the last barrels of oil in a climate destabilized world. There is no reason to believe that a nation that learned nothing positive from the genocide it was founded upon will relinquish its death grip on power, even if it brings the entire planet into ecological chaos.

One of the interesting developments under Trump, the belligerent corporatist who walked away from an ineffectual Paris Climate Accord on the heels of pipeline expansionist and drone warrior Barack Obama, is the fact the military’s attention to climate change is not confined to just one paper. Members of the military community have continued to point out the looming danger of climate change. Even into the strange days of Trump, climate has been an ongoing concern from more vocal members of the Pentagon, and has led to figures like Bill McKibben pointing to their role as advocates for addressing the climate. “…the Pentagon, when it speaks frankly,” McKibben opined, “has the potential to reach Americans who won’t listen to scientists.” Perhaps it is this understanding of the pro-military psyche of the highly propagandized American populace that led him several years earlier to pen an article for The New Republic entitled “A World at War” in which he proclaims “We’re under attack from climate change—and our only hope is to mobilize like we did in WWII.”

In his opening commentary, he attempts to capture our militarist imagination with images of a supposed war that greenhouse gases are waging against us and the planet as a whole. “Enemy forces have seized huge swaths of territory; with each passing week, another 22,000 square miles of Arctic ice disappears,” he tells us. Instead of listening to scientific and military experts, “we chose to strengthen the enemy with our endless combustion; a billion explosions of a billion pistons inside a billion cylinders have fueled a global threat as lethal as the mushroom-shaped nuclear explosions we long feared.” When McKibben assures us that this comparison is not some figure of speech, he reveals another facet of his dangerous thinking when it comes to climate change and war. “But this is no metaphor. By most of the ways we measure wars, climate change is the real deal: Carbon and methane are seizing physical territory, sowing havoc and panic, racking up casualties, and even destabilizing governments. (Over the past few years, record-setting droughts have helped undermine the brutal strongman of Syria and fuel the rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria.)”

McKibben’s primary intent appears to be one of mobilizing the American people to rise to the challenge of facing climate change, as if we are preparing for World War II. But by framing greenhouse gases, or the combustion of fossil fuels, as a wartime enemy, he commits several grave mistakes. The primary mistake is the reality that wars are not waged by greenhouse gases or machines, but by the people who produce and control the profit and power driven systems that enable their proliferation. While McKibben perceives that the image of war is useful in that it provides an opportunity to appeal to America’s wartime nostalgia and perhaps mobilize those “Americans who won’t listen to scientists,” it falls short of the more accurate perspective that it is the belief in the actual economic system and technologically driven framework which organizes the institutions of power into a war on humanity and the planet.

McKibben can’t bring himself to call capitalism, militarism, and technologically centred consumerism as enemies of the people to be resisted. To excuse him for his particular framing as a kind of practical rhetorical decision is to overlook the dangerous obfuscations that arise and tendencies which are amplified as a result of such a framework. While McKibben nurtures our dangerously sanitized vision of patriotic history, he simultaneously lets off the hook and further empowers some of the most significant perpetrators of the crisis by maintaining our faith in a mythic US military practicality. As previously mentioned, it is not simply the significant and under reported greenhouse gas emissions of the military that is the problem. It is also the diversion of needed resources to unsustainable war making. It is the creation of a global order based in mistrust and brutal competition that fuels consumerism. It is the dangerous empowerment of militarized and paramilitary security forces at a time when the world is becoming increasingly unstable.

And when McKibben characterizes President Assad as the “brutal strongman of Syria”, rather than describing his more nuanced role as a popularly supported leader in the face of US, Israeli, and Gulf State directed aggression, he moves beyond the abstractions of WWII imagery and into direct support for American imperialist interests. His tacit support for the US war machine was further evidenced when he concluded that with the emergence of “green” tech, “The day will come when blocking the strait of Hormuz or blowing up a petrol station will be an empty threat – and that will be a good day indeed.” This of course is a shot at the enemy of American and Israeli elite, Iran. What such a remark avoids is any pretense of a future without US foreign meddling, whether that be in the form of toppling leaders like Iran’s former Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh at the behest of oil interests, or the US implementation of destabilizing sanctions in more recent years. While McKibben might lament the oil wars, his alignment with popularly held US prejudices is right out of the same neoconservative playbook which spawned George Bush’s axis of evil. In a world where the destabilizing climate will become one of many factors that both increase the likelihood of war and provide opportunities to devise profit-garnering narratives of so-called “humanitarian intervention,” McKibben is making it clear that his trust ultimately lies not with the people who suffer under the boot of military aggression and capitalist exploitation, but rather with a power structure that is quite literally killing us.

Kids in Hanano, East Aleppo, 24 hours after liberation from Nusra Front-led occupation, by the SAA and allies. December 2016 [Photo: Vanessa Beeley, Source]

Playing fast and loose again with the reality of the linkages between war, environmental exploitation, and climate change, McKibben declared in an opinion piece for The Guardian: “No one will ever fight a war over access to sunshine – what would a country do, set up enormous walls to shade everyone else’s panels? …A world that runs on sun and wind is a world that can relax.” Beyond the obvious fact that wars were fought long before oil became a hot commodity, perhaps the most glaring deception in McKibben’s arsenal is that war will be significantly reduced simply by the widespread adoption of “green” tech. But if you examine McKibben’s phrasing, he doesn’t say “no one will ever fight a war over access to the components needed to manufacture green technology.” Rather, it is access to sun or wind, he says, that won’t spur bloodshed. This may be true, but he is implying for the casual reader that access to sun and wind is the same as access to raw materials and technological products that transform wind and sun into electricity. Nothing could be further from the truth, and his careful word choice is extremely deceptive. It is a bit like the kind of lie one might tell if one were operating from a war mentality, justifying the creation of false propaganda meant to rally people around a national cause that is sold as being for the greater good. “Wars can’t be fought over sunshine” makes for a clever, if duplicitous, slogan in a nation whose populace has grown less supportive of the oil wars they are funding with their tax dollars. But perhaps a bit of sleight of hand is good for the cause. The ends justify the means, as the saying goes. But do they really?

Another saying is that truth is the first casualty of war. If you are waging a war against amorphous greenhouse gases rather than acknowledging the war that has been initiated against life by technology and profit centred networks of capitalists, security forces, and politicians of all stripes, then your distorted framework sets the tone for more distortions. But as Medea Benjamin points out in her critique of McKibben’s call for a kind of wartime climate mobilization, “Some of the worst state responses to climate disruption already look like war.” As a means to demonstrate the ugliness of actual wars rather than promulgating simplistic, mythologized narratives, she refers to the Congolese forced labor which was used during WWII to extract uranium that went into the atomic bombs that would needlessly kill over one hundred thousand Japanese civilians.

McKibben assures us “…it’s important to remember that a truly global mobilization to defeat climate change wouldn’t wreck our economy or throw coal miners out of work. Quite the contrary: Gearing up to stop global warming would provide a host of social and economic benefits, just as World War II did.” As a reactive, crisis induced scramble for solutions from the same mindset that produced our problems, this kind of blind triumphalism has no time to soberly internalize both the hard limits of a growth-based economic system on a finite planet, and the deep tragedy of a world which had plunged itself into the bloodiest war in human history. Such triumphalism is ultimately incapable of seeing how the true lessons of war and the belief in a mythological progress continue to be ignored as we move into climate chaos.

This belief in a technologically driven progress which can be found in McKibben’s writing, and which often centers the discussion on an unerring belief in green jobs and economic prosperity over the reality that continued economic growth disrupts global ecologies, mirrors the kind of post WWII optimism which accompanied the so-called Great Acceleration. The Great Acceleration refers to the rapid economic growth seen during the war and the years following, which had an enormous impact on the environment. Ecologist and cellular biologist Barry Commoner concluded that, “The chief reason for the environmental crisis that has engulfed the United States in recent years is the sweeping transformation of productive technology since World War II. … Productive technologies with intense impacts on the environment have displaced less destructive ones. The environmental crisis is the inevitable result of this counter-ecological pattern of growth.” If one considers the radical changes humans have made to the planet on a geological timescale, it is easy to recognize that rather than representing a fundamental break from an older mindset, the rapid push for so called renewables is simply the machine of planetary consumption shifting gears.

In a critique of one aspect of this intensifying technological paradigm, Bill McKibben warns about the potential dangers of things like artificial intelligence in his book Falter, but when he calls the military industrial complex one of “the few places where it’s actually possible” to conduct research and development, his warnings ring hollow. In this world of great acceleration, cultures that value their modern consumerist lifestyle over unbroken forests, that don’t put up serious objections to continued growth and warfare, issue in the next wave of technological “innovation” which further speeds up the process of planetary destruction. If McKibben believes that the military will help develop the next generation battery technology to power electric cars, he should be aware those batteries emerge from a larger gestalt of full spectrum dominance, where better and faster applies first to maintaining a kind of material superiority that, if taken to the logical extension of automated warfare, threatens to launch our technosphere past the ability for humans to meaningfully react. The crisis, then, when seen through the lens of technological innovation and war, only accelerates the destruction of life.

It is in this reality, where violence and exploitation undergirds the accelerations of modern consumer society, and green tech in fact relies on raw materials lying in often contested ground, that the US Department of the Interior finalized a list of thirty five “critical minerals” in 2018. In the Summary for the final document, the department declared that “The United States is heavily reliant on imports of certain mineral commodities that are vital to the Nation’s security and economic prosperity. This dependency of the United States on foreign sources creates a strategic vulnerability for both its economy and military to adverse foreign government action, natural disaster, and other events that can disrupt supply of these key minerals.” Among the thirty five minerals considered to be part of this “strategic vulnerability” were indium, tellurium, lithium, cobalt, and the rare earth elements, all of which are important components of corporate manufactured “green” technology.

What this translates to, of course, is that while wars won’t likely be fought over sunlight, the materials needed to produce “green” technology may indeed be the subject of significant future conflicts. This becomes increasingly clear when one looks more closely at the reality on the ground. For example, the very same nation which contained the highly concentrated uranium ore exploited for the atomic bomb, a nation with a legacy of Western colonial oppression and violent internal conflict, also produces over 60 percent of the world’s supply of cobalt, which is used in the cathode of lithium ion batteries. In 1961, shortly after gaining its independence from nearly 80 years of Belgian colonial rule, the newly elected Prime Minister of the Republic of Congo, Patrice Lumumba, was assassinated with direct assistance from the United States. The result would be a decades-long rule by a US-friendly autocrat followed by his overthrow and subsequent mass violence that intersected with the Rwandan genocide in which millions of people were killed.

Violence within the Congo has long relied on the control of mines for sources of income with which to pay fighters and buy weapons and supplies. One study showed the direct correlation between mineral prices, which went up with growing consumer demand, and the rise of violence. The understanding of this connection between mining operations and violent conflict led to the creation of Section 1502 of the 2010 Dodd Frank Act, which stipulated that companies refrain from purchasing minerals sourced from conflict areas. A Global Witness study, however, found that almost 80% of companies “failed to meet the minimum requirements of the U.S. conflict minerals law.”

With the majority of large mines in the Congo currently owned by China, a nation whose supposed threat to the US was emblazoned in Obama’s strategic Asia Pivot, competition for these resources will likely only go up at a time when “green” tech is being demanded with the urgency of human survival. With an estimated 30 percent of global reserves, and 95 percent of current global production, China is also the global leader in the highly polluting regime of rare earth mineral extraction and processing. To think conflict will simply decrease at the same time there is an increased dependency on unevenly distributed “critical minerals” is beyond naive. Growing competition between the US and China in exploiting Africa’s resources are an indication of one potential conflict that lies ahead. While China increases its investment on the continent, dozens of private military contractors from countries such as the US, the UK, France, Russia, and the Ukraine are operating in a variety of African nations, protecting mines, serving as bodyguards, as well as a multitude of other security related missions.

Among those looking to capitalize on both security contracts and the increased interest in minerals is the founder of the infamous private mercenary group Blackwater, Erik Prince, who has reportedly expressed his desire to profit from cobalt mines in the Congo as well as rare earth minerals in Afghanistan.

Erik Prince: founder and former CEO of the private mercenary company Blackwater, now known as Academi

Prince has been embroiled in numerous controversies, and his involvement in the minerals trade is highly suggestive of the troubling world order McKibben is trying to gloss over. In 2007, Blackwater contractors killed 17 Iraqi civilians during what has come to be known as the Nisour Square Massacre. Three contractors involved in the killing were sentenced to thirty years in prison, one of whom would go on to serve a life sentence for murder. In 2010, Blackwater would go on to pay a $42 million settlement to the State Department which, as reported in the New York Times, was in response to crimes that “included illegal weapons exports to Afghanistan, making unauthorized proposals to train troops in south Sudan and providing sniper training for Taiwanese police officers…”.

In 2014, Prince went on to oversee the illegal creation of retrofitted crop dusting planes that could be used as part of a private aerial attack force to be contracted in Africa. As part of a counterinsurgency effort in Sudan to protect oil fields, detailed in the Intercept, “Prince’s $300 million proposal to aid [Sudan President] Kiir’s forces explicitly called for ground and air assaults, initially to be conducted by a 341-person foreign combat unit. Prince’s forces would conduct “deliberate attacks, raids, [and] ambushes” against “rebel objectives,” to be followed by “continuous medium to high intensity rapid intervention”, which would include “search [and] destroy missions.” These proposed operations, which were never fully implemented, were done under the cover of various front companies and were hidden from other executives of Prince’s own company, Frontier Services Group (FSG), who believed the contract would merely entail surveillance services.

More recently, Prince made a pitch to the Trump administration to send 5,000 contracted mercenaries to topple the government of Venezuela.

It is against this backdrop that Erik Prince announced in 2019 the formation of an investment fund that will capitalize on the increased demand for electric car batteries. Looking to bring cobalt and other minerals to market, Prince told the Financial Times, “For all the talk of our virtual world, the innovation, you can’t build these vehicles without minerals that come from generally weird, hard-to-access places.” According to Reuters, by mid-2019, a subsidiary of Frontier Services Group, in which Erik Prince serves as executive director and deputy chairman, filed with the Congolese business registry for the purpose of “‘the exploration, exploitation and commercialisation of minerals’, forest logging, security, transport, construction and ‘all financial, investment and project financing operations, both public and private.'”

In addition to looking to further exploit labor in the Congo, Prince has also reportedly been exploring the potential to profit from the spoils of a war-torn Afghanistan. Expressing a desire to privatize the war in Afghanistan, an effort which would be funded in part by increased mining operations, the details of his plan were further revealed in a BuzzFeed article, where Prince was quoted as advancing “a strategic mineral resource extraction funded effort that breaks the negative security economic cycle.”

His interest rests on a backdrop in which Afghan president Asraf Ghani in 2017 gave the green light for US corporations to begin developing the country’s mineral supply, including rare earth elements, which are used in wind turbines and LED lights. In response to the president’s enthusiasm for incoming US investment, Donald Trump’s White House issued the following statement: “They agreed that such initiatives would help American companies develop materials critical to national security while growing Afghanistan’s economy and creating new jobs in both countries, therefore defraying some of the costs of United States assistance as Afghans become more self-reliant.” Trump was counting on America’s longest war to finally begin paying off, and Erik Prince, a significant financial contributor to the Trump campaign, whose sister Betsy Devos was subsequently appointed as Secretary of Education, may end up being one those beneficiaries.

This is the reality of resource exploitation and war, where large corporations and privatized military forces work as adjuncts to the wars of nation states, reaping multi-million dollar contracts, profiting from natural resources whose sale does little to benefit the impoverished citizens of the nations they are stolen from. The economic disparity engendered by such free market predation can only lead to greater sources of conflict. And now we are being told by the IPCC that in order to have a chance at avoiding the 1.5°C aspirational target set in the Paris Climate Accord, we need to some how scale up “green” technology in order to reduce global carbon emissions to the tune of 45% by 2030. Under such seemingly impossible circumstances, one can’t help but wonder how many of the jobs to be created by the Green New Deal’s push for mass renewable energy development will include private military contractors guarding mineral mines and supply chains in order to keep profitable the nearly unquestioned human and environmental exploitation which powers our unsustainable lifestyles.

“The so-called ‘Greta Scenario’ describing net 0 carbon emissions by 2025… the demand outlook for copper is going to be significant. What’s more incontrovertible is security of supply… success in finding new sources of copper is declining. In fact, much of the known copper resources today represents ‘the work of our grandfathers.'”

While images of indigenous resistance to oil pipelines have captured the imagination of the environmental left, the reality is that land grabs in the name of “green” infrastructure is also a growing reality. The new rush to exploit the minerals of Africa is one such example. Another involves the Saami people, whose protest of a copper mine in Norway that would disrupt the land and traditional lifestyles of indigenous herders and fishers, was ignored. With the decision to permit the mine, Trade and Industry minister Røe Isaksen said, “Obviously, most of the copper we mine in the world today is used for transporting electricity. If you look at an electric car for example, it has three times the amount of copper compared to a regular car”.

While demand for access to land rich with minerals will rise, most of the pathways mapped out by the IPCC for limiting global temperature to 1.5°C incorporate the unrealistic use of massive tracts of land for capturing carbon out of the atmosphere. This is the response to a projected timeline in which emissions are not adequately brought down, and the resulting carbon overshoot must be compensated for with so called negative emissions technologies. Such scenarios paint a picture in which areas twice the size of India must be cultivated for biomass. The question is, whose land will be used? Who will be forcibly removed? Taken together, this so-called fourth industrial revolution of “green” technology has all the hallmarks of a militarily-enforced manifest destiny, in which the technologically advanced, hyper consumptive way of life for wealthy nations is violently preserved at the expense of both the planet and lives of impoverished people around the globe. In reality, the likely failure of such hail mary carbon reduction schemes will affect everyone in a rising tide of scarcity and violence, as the global elites rely upon these same kinds of security and military institutions they’ve always turned toward in order to maintain hold on a crumbling order that they packaged as our salvation.

A WKOG parody advertisement that is more and more difficult to detect in the year 2019. NGOs and “environmental leaders” are more and more, openly functioning as key instruments of US imperialism.

In addition to the fact that contested land and minerals needed for a world powered by “green” tech could easily play a role in future conflicts, so long as militaries are economically supported and culturally celebrated, fossil fuels will remain a strategic commodity for armies around the world. As a dense, portable, and storable source of energy, fossil fuels will continue to be the central source of power for military vehicles. Imagine trying to run tanks, destroyers, and fighter jets on solar or wind charged batteries. While the notion of using biofuels in the military is increasingly gaining traction, most vehicles will not run on 100% biofuels, instead requiring a mixture with a standard petroleum derivative. For example, jet fuel made from biomass, known as bioject, can only be mixed at up to a 50% blend. Furthermore, the production of biofuels remains largely energy inefficient and land intensive. The mass adoption of biofuels would likely displace arable land at a time when global population is growing, droughts and extreme weather is increasing, and fantastical schemes to sequester carbon through the cultivation of massive carbon sinks will already be driving up food prices. Rising food prices, of course, is yet another potential source of conflict, so “greening” the military is no surefire method to reduce global tensions.

And so long as militaries, whether American or otherwise, have a critical need for fossil fuels, petroleum will remain a strategic commodity. This means that even if the United States were able to somehow convert its military to be entirely fossil fuel free, if other nations remain reliant upon the use of fossil fuels even if only for their military, control of the world’s oil supply will remain a strategic objective. What all of this suggests is that far from being a preventative measure for military violence, a switch to “green” tech, will likely have little if any impact on war, and in some cases may in fact become a pretext for colonialist land grabs and armed conflict. Only a dedicated anti-war, anti-imperialist movement that intersects with environmental protection, that loudly condemns the crimes and excesses militarism and consumer culture, rather than seeing them as constructive platforms for our future on earth, can have any hope in bringing about peace, and a stable, livable world.

In April 2016, The Climate Mobilization published the paper Leading the Public into Emergency Mode: A New Strategy for the Climate Movement. The paper weighs heavy with American exceptionalism. Notes of nationalism and cultural superiority waft throughout the document. [Source]

Many Westerners have bought into the “war propaganda” of this global push for a “green” tech fueled, militarily enforced capitalism. As both the economic and environmental situations deteriorate, perhaps the push for widespread adoption will indeed reach the kind of fevered pitch Bill McKibben advocates. This could very well come at a time when the militaries which avoided substantive critique and were instead elevated as potential allies in the “climate fight” come on full display. In this future where comforting narratives like McKibben’s steer the populace away from the much darker truth, manufactured humanitarian disasters provide the palatable cover for the dirty work of securing access to raw materials needed for battery production and wind turbines by armies whose bases are hardened for sea level rise, yet whose tactical vehicles are still necessarily dependent upon dense fossil fuel power. At this time of great uncertainty, a genuine dissent which had languished under the spell of false promises of “green” technology and ignored the mass violence that underpins modern industrial society, emerges out of necessity from the growing direness of global crop failures and economic breakdown. This growing dissent, which threatens the illegitimate power held by the global elites, is met with heavy repression that draws upon decades of unimpeded surveillance tech implementation, the militarization of global police forces, and the use of private security. The participants in such a movement would have done well to have heeded the reality that the private contractor TigerSwan, which had operated inside of Afghanistan and Iraq in support of the US war efforts, had been mobilized against protesters during the militarized crackdown at Standing Rock under the watch of President Obama. Nations which had celebrated their institutions of violence while dismissing the real threats such a framework posed, would fall under the shadow of the very security forces they had funded to the detriment of systemically oriented solutions.

This is the nightmare that any genuine climate movement would openly seek to avoid, but it is a nightmare that is well under way. Rather than obfuscating the multifaceted threat that a culture of tech driven consumerism and militarism plays in an increasingly resource scarce, climate destabilized world, such a movement would seek to highlight those connections between planetary exploitation, violence, and the climate crisis as a means to deescalate the potential for future global wars, all while acknowledging the reality that climate catastrophe is now an inevitability. It is increasingly clear that we will not stay below the 1.5°C aspirational target set forth in the toothless Paris Climate Accords, and the 2°C target will not likely be respected either. Widespread disruption is now an inevitablility. Which begs the question, what sort of framework will humanity adopt in approaching this future? Will it be one of a triumphal war rhetoric, “practical” alliances with the military industrial complex, and the downplaying of the disastrous consequences of militarism?

Clive L. Spash, WU Vienna University of Economics and Business, Vienna, Austria, This Changes Nothing: The Paris Agreement to Ignore Reality, Globalizations, 2016 Vol. 13, No. 6, 928–933

Climate change at its core is about conflict. It is a conflict between how humans live with each other and with the planet, and this conflict builds on centuries of violence and exploitation that are enmeshed, often unseen by the privileged, within the economic, social, and political systems to this day. We can either face our own discomfort and confront the structures of violence that have brought us to this turning point in human history, or we can soothe ourselves with comfortable narratives and allow the internal conflicts inherent in the system to catapult us far beyond the breaking point. With the primary focus currently being on narrow and insufficient technological approaches to a holistic problem of violence and exploitation, a broad and genuine environmental and social justice movement has yet to materialize. While climate catastrophe is now inevitable, its scale has yet to be determined. The underlying social conflicts we refuse to engage with today become the amplified armed conflicts of tomorrow. Only when people join together, rejecting mass consumer culture embodied in capitalism and enforced through militarism, to instead create leverage through sustained civil disobedience and the creation of ecologically minded communities that view life as sacred, can the kind of radical demands needed for the potential of a livable future be realized.

In all likelihood, such resistance will be met with the kind of structural State (and non State) violence that Bill McKibben ignores, but to refrain from the kind of resistance that opens the door to structural change, and to ignore the reality of deep structural violence, only guarantees a violent collapse, as heavily armed and economically stratified societies run up against the hard limits of physics. Indeed, we are now faced with the potential that no matter how great our efforts, the everyday materialism and violence that makes our system function, and the steepness of the changes now required, may prove too daunting to adequately address. How people choose to deal with this reality is yet to be seen, but it is better to have such conversations now than in the midst of bloody social breakdown. Solace can be found in the solidarity of peers, among those who would both work for a better future or stand at your side when such a future is no longer possible. Rather than masking reality with feel good propaganda that profits the wealthy, it is our decision to move with a fierce and loving intent from within a darkness we are able to acknowledge, that gives us the capacity to be both carriers of genuine transformation in a troubled yet salvageable world, and steadfast companions in one that is doomed.

[Luke Orsborne contributes time to the Wrong Kind of Green critical thinking collective. You can discuss this article and others at the Climate Change and War group on social media.]

[1] Continued: “These mining + processing operations have left a legacy of potential exposures to uranium waste from abandoned mines/mills, homes and other structures built with mining waste which impacts the drinking water, livestock + humans. As a heavy metal, uranium primarily damages the kidneys + urinary system. While there have been many studies of environmental + occupational exposure to uranium and associated renal effects in adults, there have been very few studies of other adverse health effects. In 2010 the University of New Mexico partnered with the Navajo Area Indian Health Service and Navajo Division of Health to evaluate the association between environmental contaminants + reproductive birth outcomes. This investigation is called the Navajo Birth Cohort Study and will follow children for 7 years from birth to early childhood. Chemical exposure, stress, sleep, diet + theireffects on the children’s physical, cognitive + emotional development will be studied. Billboard: JC with her younger sister, Gracie (who is a NBCS participant). #stopcanyonmine” [Source]