Apr 14

20180

Avaaz, Humanitarian Agencies, Imperialist Wars/Occupations, Neo-Liberalism and the Defanging of Feminism, Oxfam, Social Engineering, The International Campaign to Destabilize Syria, Whiteness & Aversive Racism

Avaaz MSF Purpose Res Publica Save Darfur Save the Children Syria White Helmets

The New Humanitarianism: The Imperative to ‘Act’ and to ‘Act Now’

April 14, 2018

An Excerpt from the book Celebrity Humanitarianism – The Ideology of Global Charity by Ilan KapoorFirst [2013]

‘Ilan Kapoor’s stunning new book exposes the most appealing – and thus most dangerous – sacred cows of contemporary ideology: the humanitarian actor, the billionaire philanthropist, and the NGO. Kapoor shows that it is precisely where we feel most emotionally satisfied that we must be most suspicious. Celebrity Humanitarianism represents a landmark in the critique of ideology and a decisive blow in the struggle against apolitical ethics.’ — Todd McGowan, University of Vermont, USA

Since the end of the Cold War, there has been an explosion of international NGOs, particularly development and humanitarian ones, leading to the rise of what is termed ‘global civil society’. In large measure, this is due to the ascendancy of neoliberalism, which has seen NGOs fill the many gaps created by government cutbacks and privatization. But in part, it is also the result of the intensification of globalization and the information economy, which has opened up possibilities for greater borderlessness’. Not content with doing only aid and development work, NGOs have carved out an increasingly more activist and interventionist role for themselves in the global arena. This trend is what has been called ‘the new humanitarianism’.

Central to the new humanitarianism is a security discourse, which divides the world, not so much along the lines of wealth vs. poverty as it used to, but more in terms of stability vs. threat. Mark Duffield argues that the security discourse is constructed on the basis of the metaphor of the ‘borderlands’ (i.e. the Third World), an imagined geographic space of instability, excess, and social breakdown, which poses a threat to the metropolitan areas (2001: 309).

The borderlands are depicted as violent and unpredictable, or at least always a potential danger; they are the source of many of the problems seen to plague global security, including drug trafficking, terrorism, refugee flows, and corrupt/weak/rogue states.

Accordingly, the point of international intervention is to tame and manage instability. In this scenario, poverty, corruption, and refugee flows are to be feared much more than alleviated. Development and humanitarianism are seen not as problems of reducing inequality or protecting the most vulnerable, but as technologies of security, which function ‘to contain and manage underdevelopment’s destabilizing effects’ (Duffield 2007: ix, 24).

The practical outcome of this new humanitarianism is a significant shift away from respecting national sovereignty and towards external intervention in the Third World: it means neglecting international law, or obeying the ‘higher’ moral law of humanitarianism, under the guise of the ‘responsibility to protect’ (cf. Mamdani 2009: 274; Watson 2011: 5). In other words, new humanitarianism has increasingly become neoimperialism, allowing the West to ‘transform conflicts, decrease violence and set the stage for liberal development’ (Duffield et al. 2001: 269). Not just a Third World country’s foreign policy, but now also its domestic economic or human rights situation is seen as a credible threat (Duffield 2001: 311), recalling colonialism’s ‘civilizing mission’ to eradicate ‘barbaric’ Third World cultural practices such as widow-burning or infanticide. More often than not, the form of external intervention is military, that is, armed intervention parading as humanitarian rescue mission. The post- 9/11 War on Terror has only escalated this trend, enabling the possibility of ‘unending war’ to secure the borderlands (e.g. Iraq, Afghanistan) (Duffield 2007: 131). Illustrative of unending war is the following list, compiled by Watson (2011: 4), enumerating the countries for which humanitarianism has been used to justify military intervention in recent years: Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, Angola, Mozambique, Kosovo, East Timor, Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Zaire, Sudan, Côte d’Ivoire, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

NGOs are firmly enmeshed in this security–humanitarian network. For the past two decades particularly, the private–public linkages between Western states, UN agencies, private firms, militaries, and NGOs has grown. In fact, as Duffield puts it, the securitization of development/humanitarianism ‘has been of central importance for legitimising the growing involvement of non-state actors’ (2001: 312; cf. Watson 2011: 3–4). And NGOs have become not just accomplices in this network, but key players. Mamdani goes so far as to argue that the new humanitarianism is the ‘twin of the War on Terror’ (2009: 274), with groups such as Save Darfur as pivotal facilitators. NGOs have pushed for and capitalized on the vast resources directed at emergency and security operations around the globe. Many such operations (e.g. in Afghanistan, Haiti, Bosnia) have been ambitious and well coordinated, with relief agencies working alongside military or peacekeeping campaigns.

Above: Res Publica (Avaaz) calling for a Darfur intervention and criminal indictment. August 3, 2004 screenshot: “Only one thing will stop the killing in Sudan: an immediate international intervention” … “Click here to sign a petition calling for humanitarian intervention Darfur” [WKOG screenshot]

The imperative to ‘act’ and to ‘act now’ is central to these NGO campaigns.

To be sure, beginning mainly in the post-World War II era, organizations such as Oxfam, ActionAid, and MSF were created to respond to global crises, ranging from armed conflicts and epidemics to ‘natural’ or man-made disasters. Whether we are talking about the 1949 Palestinian refugee situation, the 1967 Nigerian civil war, the 1984–85 Ethiopian famine, or the more recent 2005 Pakistan earthquake, emergencies have become an opportunity for humanitarian NGOs to function and even expand. Indeed, they have been able to justify and aggrandize themselves based on what Duffield refers to as a ‘permanent emergency regime’ (2007: 25, 47–49, 219). All of them rely on a ‘threaturgency narrative’ to ‘legitimize their functions’ (Watson 2011: 9); it is this narrative that allows them to identify and categorize the disaster (e.g. as an impending famine or a pressing refugee crisis), as well as publicly highlight the humanitarian duty to save lives or assist ‘populations in distress’, as MSF puts it (http://www.msf.org).

One of the most poignant recent examples of the construction of emergency discourse is that of the Save Darfur Coalition, especially during the 2004–7 period. The Coalition relied on highly charged rhetoric to issue its emergency call for international intervention. The first move, as Mamdani underlines (2009: 64–65), was to categorize the conflict in the Darfur region as racially motivated: the government-armed ‘Arab Janjaweed militia’ were reportedly perpetrating violence against ‘black-skinned non-Arabs’. Such stereotyping became pervasive in Western public discourse and was often repeated by the mainstream press, including The Washington Post (Mamdani 2009: 64; cf. Hassan 2010: 98). Mamdani notes (2009: 6) that this ethnicized/racialized framing has its origins in the colonial tradition of racializing the peoples of Sudan for political purposes (i.e. as a divide and rule strategy); it is a framing that, in the contemporary global conjuncture, only served to reinforce the discourse of the War on Terror, demonizing Islam and Arabs, and pressing for immediate counter-terrorist action.

Above: Res Publica (Avaaz) March 8, 2005 screenshot: “Sign a petition below … over 18,000 signatories in the last week!” [WKOG screenshot]

The Coalition’s second discursive move was to characterize the Darfur situation as ‘genocide’ (despite evidence to the contrary, as we shall see below). It is the deployment of this culturally and politically charged term that, almost single-handedly, brought together such a large and diverse range of US-based organizations that made up the Coalition (see above), while catching the attention of the media and politicians alike (cf. Save Darfur Coalition 2011). After Save Darfur’s ‘genocide alert’ in 2004, events quickly gathered pace: a student-led divestment campaign was organized, a large Save Darfur Rally To Stop Genocide was held in Washington, DC, and an impassioned plea (by George Clooney) was made to the UN Security Council for international intervention. In 2007, the rhetoric was ratcheted up. The Coalition criticized China for its strong support of the Sudanese government, with a campaign that included taking out full-page advertisements in The New York Times and Mia Farrow denouncing the upcoming Beijing Olympics as the ‘Genocide Olympics’.

The overall effect of this emergency discourse was to exercise tremendous pressure on political leaders in the US and around the world. Secretary of State Colin Powell testified in front of the Senate Relations Committee that genocide was being committed in Darfur. The US Congress agreed, pushing for political and economic sanctions for Sudan. Meanwhile, the UN Security Council referred the Darfur case to the International Criminal Court, sent UN peacekeeping troops to Sudan, and following China’s change of position on the Council in the face of public pressure, established a larger joint UN–African Union peacekeeping mission, with financial support from the US Congress (cf. Flint and de Waal 2008: 181, 280; Haeri 2008: 35–37).

One of the most troubling features of this NGO emergency discourse is its tendency towards militarization and war. The imperative to act ‘now’ tends to provide added impetus and rationale for militarized intervention. We are familiar with NGOs providing relief work in war zones, in which they must sometimes coordinate with warring factions to deliver aid programs. We are also familiar with the use of army troops in non-military crises such as the Asian Tsunami in 2004 or Hurricane Katrina in 2005 (to keep law and order, or help NGOs distribute food aid). Increasingly, as Watson argues, ‘states and the international community have institutionalized a militarized response through the establishment of specialized military entities such as the United States Foreign Disaster Assistance or the Canadian Disaster Assistance Response Team’ (2011: 9).

But what is relatively new and noteworthy is the call by humanitarian NGOs for military intervention – a phenomenon described by the paradoxical concept, ‘humanitarian war’. It is a concept that, as Vanessa Pupavec notes, NGOs themselves helped legitimate, especially through their demands for military intervention in the Balkans during the 1990s (2006: 263). Thus, MSF appealed for military action in Bosnia in the mid-1990s, while Save the Children lobbied Western governments for armed intervention in Kosovo in the late 1990s (Pupavec 2006: 255). Since that time, several other similar calls have been made. Of particular note are Oxfam’s demand, in relation to the Darfur situation, for a broader interpretation of the UN Charter on the principle of non-interference to include intervention, and Save Darfur’s outright plea for a no-fly zone and Western military action. In fact, ‘Out of Iraq and Into Darfur’ became a common Save Darfur slogan. Pupavec points out, in this regard, that NGOs were quick to criticize the failure to obtain UN Security Council authorization for military intervention in Iraq, but were only too willing to ignore such authorization when they demanded military ntervention in Kosovo and Darfur (2006: 266).

Above: Res Publica (Avaaz): “SUCCESS!! – Humanitarian Intervention in Darfur” … “SUCCESS!! – International Criminal Court to Prosecute Architects of Genocide in Darfur” [February 10, 2006 screenshot]

If rhetorical demands for action raise the stakes, resulting in the militarization of the new humanitarianism, so do media demands for spectacle. The mediatization of NGO emergency work – that is, the drive not just to act now, but also to be seen to be acting now – adds greater urgency. NGOs may well be responding to save lives, but they are also playing to the global media and public. MSF’s témoignage (witnessing) after all, is about witnessing not just on behalf of disaster victims, but also for the media/public. This recalls our earlier arguments about the entertainmentization of humanitarianism – the pressures to create ‘megaspectacles’, to satisfy seemingly insatiable appetites for suffering, death, and disaster. The militarization of emergency work only supplies further fuel to this fire, aiding and abetting the spectacularization of violence and war. In this regard, Henry Giroux contends that we are witnessing a new phase in the society of the spectacle, that of the ‘spectacle of terrorism’ (2006: 26).

According to him, a ‘visual culture of shock and awe has emerged’, which celebrates violence in the form of night bombing raids, hostage takings, and beheadings, or the destruction of public buildings (2006: 21, 24).

The pressure to create spectacle, then, means that spectacular NGOs are not simply observers or objective relays in delivering humanitarian aid; they are full-fledged actors, identifying emergencies and constructing them for public consumption (cf. Keenan 2002: 5). Add militarization to this mix, and you move from the imperative to act now and be seen to be acting now, to an imperative to be seen to be acting now, militarily if needs be (or preferably?).

The systemic and symbolic violence of spectacular NGOs

Three friends are having a drink at the bar. The first one says, ‘A horrible thing happened to me. At my travel agency, I wanted to say “A ticket to Pittsburgh!” and I said “A ticket to Pissburgh!”’ The second one replies, ‘That’s nothing. At breakfast, I wanted to say to my partner “Could you pass the sugar, honey?” and what I said was “You dirty fool, you ruined my life!”’ The third one concludes, ‘Wait till you hear what happened to me. After gathering the courage all night, I decided to say to my spouse at breakfast exactly what you said to yours, and I ended up saying “Could you pass me the sugar, honey?”’

(adapted from Žižek 2004b: 61)

Often, the most traumatic situations are not necessarily the outwardly perceptible ones (i.e. the gaffes of the first and second interlocutors in the joke), but the less obvious ones (i.e. the repressed content in the outward politeness of the third). As Paul Taylor suggests, telling are the moments ‘in which nothing of substance is said… in that non-utterance resides all manner of psychologically destructive forces’ (2010: 93).

And so it is with spectacular (humanitarian) NGOs: it is most often in these organizations’ non-utterances that ideological violence is to be found. The spectacle of NGO humanitarianism is revealing not simply for what it shows, but more importantly for the violence it often ignores, takes for granted, or disavows. Žižek distinguishes two types of violence: (i) ‘subjective violence’, which is directly visible and identifiable (e.g. emaciated babies, physical destruction in the wake of a hurricane); and (ii) ‘objective violence’, which is less immediately perceptible (2008a: 1–2). Objective violence is itself made up of ‘systemic violence’, which refers to our often slow yet steady social oppressions (e.g. gender exclusion, wage discrimination, the daily grind of alienating work), and ‘symbolic violence’, the violence inherent in our systems of representation (e.g. the way in which an image of a starving child can hide as much as it reveals). The crucial point for Žižek is that objective violence is what is required for the ‘normal’ functioning of our social and economic systems. In other words, systemic and symbolic violence is the background against which subjective violence happens: objective violence ‘may be invisible, but it has to be taken into account if one is to make sense of what otherwise seem to be “irrational” explosions of subjective violence’ (Žižek 2008a: 2). Accordingly, I’d like to highlight the systemic and symbolic violence of humanitarian NGOs, violence which serves as backdrop to their spectacle.

The systemic violence of humanitarian NGOs stems, at least in part, from the very nature of their work – short-term emergency operations that attempt to rescue people from immediate danger, but make no attempt to address the broader or underlying causes of such danger. As MSF’s James Orbinsky readily admits, MSF action ‘takes place in the short term’ with limited objectives in the wake of a crisis, ‘but does not itself attempt to solve the crisis’ (2000: 10). The problem is that such an approach is premised on what was earlier denoted as a ‘permanent emergency regime’: rather than working themselves out of a job, NGOs depend (and count) on more and more crises.

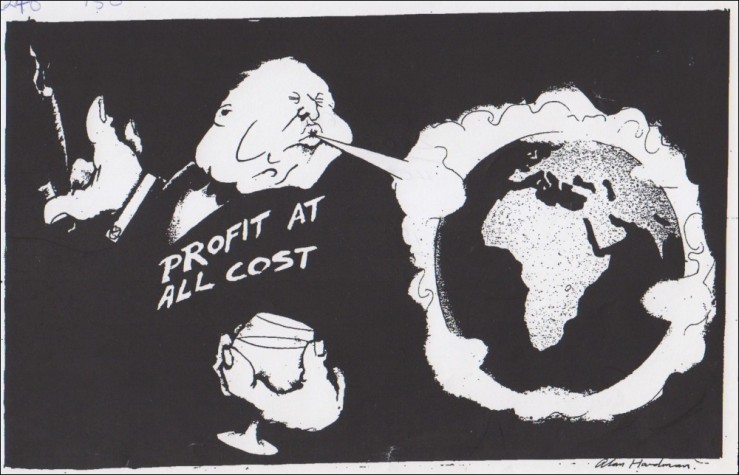

They have every interest in global neoliberal capitalism’s continued production of emergencies, which enables and legitimizes their spectacular humanitarianism. In this sense, the NGO-ization of humanitarianism (and development) may have less to do with finding effective solutions to problems than a way of keeping the humanitarian business in business.

True, some humanitarian NGOs do carry out broader ‘development’ programming, alongside their short-term relief and advocacy work. For example, MSF organizes a campaign to make cheaper generic drugs more readily available to Third World countries (cf. http://www.msfaccess.org), and Oxfam runs a host of projects in gender equality, health, and education around the world (cf. Oxfam UK 2011). But as pointed out in Chapters 1 and 2, most of these initiatives are depoliticized; they steer clear of, say, anti-capitalist/anti-racist critique, or unionization of workers (or women), in favour of tamer and nonthreatening areas such as mainstream human/gender rights and education. As Issa Shivji contends, in Sub-Saharan Africa issues of equality and equity are banished to the ‘realm of rights, not development’; that is, rights are a question of NGO ‘advocacy’, ‘not a terrain of people’s struggle’ (2006: 35). Moreover, many NGO development projects (e.g. job training, micro-credit) are ultimately an attempt at integrating subaltern groups into global capital; as James Petras puts it (1999: 432), they help corner ‘a new segment of the poor’ (e.g. young people, marginalized women, landless farmers, the urban poor), binding them to market entrepreneurialism. The result once again is a reaffirmation of the status quo, whose systemic violence is the basis for humanitarianism. And so the cycle continues … (I am not, of course, suggesting that humanitarian advocacy/relief and development should not happen, or that people must not be assisted in disasters; the problem is the significant institutional interests in people’s ongoing suffering or dispossession, and the enormous investments made in addressing the symptoms rather than the cure.)

This myopic and status quo approach is integral to the symbolic politics of humanitarian NGOs, too. The spectacularization of their relief and advocacy work is notable for what it includes as much as what it excludes. There is, first, the tendency (underlined earlier) to ‘sell’ stories and images that are visually and sound-byte friendly. Spectacles involving celebrities, poverty-stricken people, crying mothers/children, gun-toting soldiers, or war-ravaged landscapes tend to be given priority. Most often, the resulting sensationalized images/stories are serialized and repeated to achieve maximum public and media spread and exposure. As one NGO media person puts it, ‘the misery of the victims of famine, flood, war, and plague must be underlined, perhaps even exaggerated, if [the organization] is to attract sufficient public attention’ (quoted in DeChaine 2002: 361). In this regard, MSF has been criticized for its sensationalized stories, causing some to pejoratively characterize the organization’s press officers as ‘catastrophe babes’, ‘whose motives are said to be driven more by the market than by the crises’ (DeChaine 2002: 360). Such tendencies illustrate well the symbolic violence noted above, fetishizing and commodifying the outwardly visible (i.e. ‘subjective violence’) in the service of the society of the spectacle.

More often than not, the stories and commodity-images produced by NGOs resort to classic hero narratives, in which the NGO-as-hero/celebrity overcomes adversity (obstacles, enemies, crises) to save hapless victims. All the characters are clearly identifiable: the saviour-heroes are the aid workers, human rights advocates, and volunteer doctors/nurses; the enemies/adversaries are ‘natural’ disasters, or corrupt and authoritarian governments/leaders (e.g. the Janjaweed militia and President Al-Bashir, in the case of the Save Darfur narrative); and the victims are women, children, and dispossessed communities. Robert DeChaine states, for instance, that MSF’s credibility as a humanitarian agency hinges at least in part on ‘its ability to establish a perception of its volunteers as courageous, ideologically pure, morally committed agents of change. They are saviors, champions of the voiceless, who knowingly and willfully face the morally unrighteous enemies of humanity’ (2002: 362).

The creation of victims is key, and the humanitarian spectacle manages to never run out of them. Debrix argues that what transnational humanitarian NGOs such as MSF create when they intervene across state boundaries are ‘spaces of victimhood’, both spatial and symbolic: ‘Under the guise of reaching “victims” the world over, MSF constructs new spaces – humanitarian zones – inside which individuals in distress are identified as “victims”, are sorted out, and become recognisable as generalised examples of human drama’ (1998: 827). The establishment of refugee camps, famine sanctuaries, and the like, are meant to clearly demarcate these spaces, so that the victims can be triaged, categorized, treated, managed.

The people shepherded into these zones tend to be constructed as passive beneficiaries. Rarely do they have a voice; most often, it is the NGOs that speak and ‘witness’ for them. In the Darfur debacle, for example, there was a notable absence of any articulate Sudanese or indeed Darfurian voices; as Salah Hassan points out, the discourse was dominated by ‘Western celebrity activists, aid workers, and other self-appointed experts and spokespersons, thus reconfiguring the “white man’s burden” in a significant way’ (2010: 97). Faced with such persistent victimization, it should hardly be surprising that NGO saviourheroes have sometimes been received by disaster ‘victims’ with hostility rather than thanks, as in the case, for example, of Somalia in 1992 or Iraq after the 2003 invasion (Watson 2011: 14).

Kate Manzo (2008) underlines how often humanitarian NGOs resort to the use of child iconography (usually close-ups of single children’s faces). Think of the 1960s ‘Biafra child’, the 1980s ‘Ethiopia child’, or the current-day Plan/World Vision/Save the Children poster child. Child imagery has become the face and brand of NGO humanitarianism (cf. Chapter 1). Here too, the child tends to be depicted as victim, with children’s commodity-images deployed to evoke innocence, dependence, suffering (Manzo 2008: 636). Frequently, the child is meant to stand for the Third World, crying out to be helped and saved. Such paternalism only reproduces colonial tropes of infantalization of the colonies to rationalize Europe’s ‘civilizing mission’.

The production of these black-and-white stories and images, with plainly identifiable heroes, adversaries, and victims, makes for the ideal humanitarian morality tale. Drama and sensationalism permit clear and simplified messaging, enabling the audience to take sides, claim moral indignation at the situation, and feel good about its support for NGO humanitarianism. Mamdani likens this to a kind of pornography, which in the case of Save Darfur yielded a highly moral movement that appealed to people’s self-righteousness rather than political analysis (2009: 56–57; cf. Flint and de Waal 2008; DeChaine 2002: 358–59). Moral campaigns tend towards depoliticization, opting (as we have seen) for short-term, managerial, and emergency/militarized solutions. Pupavec contends that moral advocacy avoids ‘the stresses and responsibilities of implementing assistance programmes on the ground … In other words, advocacy can in some cases represent a disingenuous flight from responsibility for social problems, rather than deeper engagement with them’ (2006: 266).

The problem with the moral spectacle is precisely that it is less concerned with analysis and understanding than with taking sides and issuing calls to action. Manichean tales simplify, mystify, and ignore the often highly complex politics of emergencies. The focus on the outwardly visible and the spectacular, on special effects and sound-bytes, avoids layered, substantive, and mediaunfriendly investigation. Sensationalized media reports tend to decontextualize and homogenize, telling the story for its universal message, not its specific content: thus, for instance, earthquake ‘victims’ stand as ‘global victims’, so that the disaster ‘is made into the general condition of humankind’ (Debrix 1998: 841, 843). Media/NGO stories tend to linger on the photogenic, privileging physical destruction. In the case of the 2004 Asian Tsunami, Watson finds that the disaster was presented in the media as ‘natural’, ‘unpreventable’, ‘indiscriminate’, or ‘random’, when in fact the physical destruction and human suffering had as much to do with human activity and social systems (e.g. use of poor building materials, especially in poorer neighbourhoods): ‘the physical evidence is used to tell a particular story – one that, in essence, speaks for itself in a way that is de-historical and de-political’ (2011: 14–15).

Above image from the Avaaz website: “Libya No-Fly Zone: As Libyan government jets drop bombs on the civilian population, the UN Security Council will decide in 48 hours whether to impose a no-fly zone to keep Qaddafi’s warplanes on the ground.” [Emphasis in original]

What is left out of the NGO/media stories are the un-photogenic details, the ‘boring’ particulars of the daily grind of people’s lives, the recurring patterns of alienation or marginalization. Historical knowledge is a no-no: ‘spectacular time’ militates against ‘historical time’, because the former must organize information ‘through the media as dramatic events that are quickly displaced and forgotten’ (Stevenson 2010: 162). When there is interest in details, the media usually home in on the personal (i.e. issues of identity, individual tragedy, etc.) or the gory (i.e. violence), rather than broader politics. In the 2004 Asian Tsunami, Watson finds that the media tended to fetishize human-interest stories (e.g. personal and family tragedies), devoid of any social or political context, and to sometimes suggest that ‘victims’ were responsible for their own plight (2011: 14). Moreover, all tsunami ‘victims’ were treated the same, ignoring the fact that local residents and Western tourists were differently impacted, and that local women and children, in particular, were the worst affected: the ‘human-tragedy component served to tie all the human victims together: Westerners and locally affected populations … [thus obliterating] the different sources of vulnerability for the two groups’ (Watson 2011: 14–15). Similarly, in the Hurricane Katrina crisis, Tierney et al. (2006) find that the media focused almost exclusively on issues of looting, poverty, and racial tensions, and had almost nothing to say about recurring state cuts for infrastructure and social services in the worst affected, low-lying, and mainly poor black neighbourhoods. Concentrating on ‘secondary malfunctions’ and ‘subjective violence’ – poverty, crime, corruption, individual trauma – as opposed to the ‘objective violence’ of, say, inequality and broader political economy, is a recurring ideological strategy that we have observed before. ‘Under the guise of exposing global trauma and injustice in spectacular detail, genuine consideration of the key political and economic causes is displaced’ (Taylor 2010: 131).

Such tendencies to ignore key details or broader contexts are integral to the types of photos or films produced by NGOs. Invariably, these are either largescale images (i.e. aerial or wide-angle shots) of landscapes and neighbourhoods, or close-ups of individuals and faces. This toggling between the bird’s eye view and the shrunk/miniaturized view, as Jim Igoe argues,

allows for the simultaneous presentation of problems that are so large they demand the attention of the whole of humanity, while identifying specific groups of people who are their perpetrators … Missing from these presentations are the complex and messy connections and relationships that are invisible in both the open-ended vastness of spectacular [landscapes] and the compelling specificity of prosperous villagers. (2010: 382)

It is not just the broader contexts of emergencies that spectacular humanitarianism ignores; it is also that some emergencies tend to be neglected altogether. During the Asian Tsunami, for example, the Western press focused almost exclusively on known tourist locations across the region, overlooking the devastation in ‘lesser-known countries and localities’ (Cottle and Nolan 2007: 879). The other, more telling recent example here is the Congo, where over four million people have died over the last decade, but which has received little attention from the press. Žižek writes in this regard that:

The Congo today has effectively re-emerged as a Conradian ‘heart of darkness’. No one dares to confront it head on. The death of a West Bank Palestinian child, not to mention an Israeli or American, is mediatically worth thousands of times more than the death of a nameless Congolese. (2008a: 3; cf. Mamdani 2009: 63)

The various manifestations of symbolic and systemic violence outlined above are revealing of the ideology of spectacular NGOs. For what is ideology, in the Žižekian sense that we mean it, other than the production of spectacular images and smooth spaces (i.e. humanitarian zones) to cover up the Real (broader political economy, long-term political alternatives, Western complicity)? The glossy photos and sensational headlines help create pure, untarnished, and moral humanitarian fantasies to be commodified and sold. The smooth spaces (refugee camps, etc.) help manufacture artificial humanitarian sanctuaries where ‘victims’ are categorized, controlled, and ultimately served up as advertisements for the likes of MSF, Save Darfur, or Save the Children (cf. Debrix 1998). The NGO/media spectacle helps to unify and stabilize reality, disavowing anything that disturbs the humanitarian dream-fantasy, is discomforting to the public, or threatens the neoliberal global order. Outwardly visible, subjective violence may well be shown, or even fetishized, but that it is symptomatic of a dirty underside, a broader underlying objective violence, is glossed over.

Of course, spectacular NGOs hide behind their faux objectivity and nonpartisan humanitarianism to repudiate any accusations of political ideology. Yet, as we have seen, their very presentation of reality through their stories and images is already an ideological construction of it (cf. Taylor 2010: 83). They create (the public view of ) emergencies and disasters in advance, so that ‘reality’ and the audience’s perception of it are one and the same (cf. Žižek 1994b: 15). Thus, Debord writes, ‘For what is communicated are orders: and with perfect harmony, those who give them are also those who tell us what they think of them’ (1990: 6).

[Ilan Kapoor is a Professor of Critical Development Studies at the Faculty of Environmental Studies, York University. He teaches in the area of global development and environmental politics, and his research focuses on postcolonial theory and politics, participatory development and democracy, and more recently, ideology critique. He is the author of The Postcolonial Politics of Development (Routledge 2008), and more recently, Celebrity Humanitarianism: The Ideology of Global Charity (Routledge 2013). He is currently writing a book on psychoanalysis and development.”]

+++

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0PrT5P8Dftw&feature=youtu.be&t=1m54s