Nov 26

20110

Humanitarian Agencies, The Occupation of Haiti

Aid Alternatives Canadian Foundation for the Americas Centre for International Studies and Cooperation CIDA Couchiching Institute on Public Affairs Development and Peace Freedom Network Haiti International Legal Resources Centre Québec Association of International Cooperation Organizations Rights and Democracy Roundtable on Haiti USAID

How USAID Undermines Democracy in Haiti

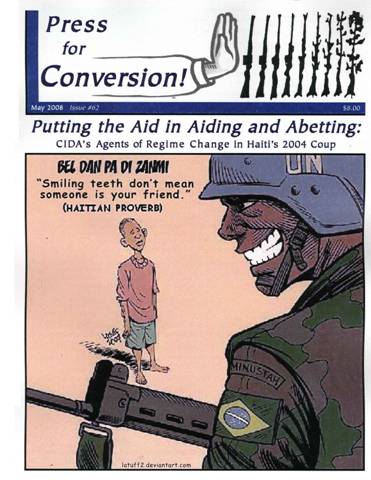

The image above is from the article “Putting the Aid in Aiding and Abetting: CIDA’s Agents of Regime Change in Haiti’s 2004 Coup”. CIDA is the Canadian version of USAID. #62 (May 2008)

November 18, 2011

by Leslie Mullin, Pambazuka

The US Agency for International Development (USAID) is an arm of the US State Department. Founded in 1961, USAID serves as a ‘velvet glove’ for US foreign policy. The political bias of its operations in Haiti goes back decades. Here are ten things to know about USAID in Haiti:

1. USAID paid millions to Haiti’s ruthless dictator, Francois ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier, aimed at shoring up US influence in the region after the Cuban revolution. Thirty to fifty thousand people were killed under Duvalier’s regime while aid funds were siphoned into the private coffers of the Duvalier family. Under Duvalier, assembly production for American corporations became the blueprint for Haiti’s economic dependence on the US. The formula, essentially unchanged to this day, backs Haiti’s ruling elite while turning Haiti into a low-wage export-focused economy that creates profitable business opportunities for foreign investors. Haitians call it ‘the death plan’.

2. USAID backed Duvalier’s son, Jean-Claude ‘baby doc’, when he took over in 1971, with plans to promote Haiti as the ‘Taiwan of the Caribbean’. American taxpayers provided millions to build an infrastructure to lure US manufacturers to open assembly plants, taking advantage of Haiti’s high unemployment, political repression, and wages of 14 cents an hour. The consequences were profits for US business and the Haitian super rich. By the time of Duvalier’s fall, Haiti was the world’s ninth largest assembler of goods for US consumption, and the largest producer of baseballs.

3. USAID sabotaged Haiti’s domestic food production. USAID has a major impact on Haiti’s economy, both directly and as an agent for big financial institutions like the IMF. Nowhere is this more clearly demonstrated than Haiti’s food system. As recently as 30 years ago, Haiti produced most of its own food. Then, in the early 1980s, USAID undertook a plan to redirect Haiti’s domestic food production towards export crops. The idea, tied to Ronald Reagan’s Caribbean Basin Initiative, was to integrate Haiti into the world market via agro-industry and export manufacturing.

With full awareness of its dire impact on Haitian peasants, USAID experts set about to shift 30 per cent of Haiti’s cultivated land from food produced for local consumption to export crops. As Haiti’s rural economy unravelled, impoverished peasants fled to the capital city.

Competition from cheap imports and the absence of policies to promote production led to a rapid decline in Haiti’s food production. By 2008, local food production amounted to 42 per cent of Haiti’s food consumption, compared to 80 per cent in 1986. At the same time the value of US agricultural exports to Haiti began to increase – from $44 million (1986) to $95 million (1989). Recently, USAID was helping agriculture officials boost Haiti’s production of mangoes – for export to the United States.

4. USAID enforced trade liberalization policies that undercut Haiti’s rice industry while promoting American rice. In 1986, USAID conditioned aid to the ruling military junta on lowering rice tariffs, while advising the government to remove the little assistance it gave to Haitian farmers. Haiti slashed its rice tariff from 35 per cent to 3.5 per cent (1986) and to 1.5 per cent (1995). Not only were Haitian farmers hurt, but American producers and grain sellers profited. Cheap, heavily subsidised ‘Miami’ US rice flooded Haitian markets, and Haitian rice production began to drop. Until the early 1980s, Haiti produced the majority of its own rice, but Haiti is now the fourth largest importer of American rice.

One beneficiary was the Rice Corporation of Haiti (RCH), owned by Erly Industries – a massive US agribusiness and the largest marketer of American rice. In 1992, RCH secured a nine-year contract to import rice from Haiti’s illegal coup government – a military junta responsible for the deaths of thousands of Haitians. RCH was managed at the time by the former director of the Caribbean Basin Initiative (1982-1988), with powerful friends in Washington like Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Jesse Helms (R-NC).

Erly Industries gained another foothold in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake when USAID awarded an Erly subsidiary, Chemonics, the contract to implement the 2009 USAID ‘winner’ program. Chemonics is an international consulting firm that relies on USAID for 90 per cent of its business. Winner is another example of USAID’s reckless assault on Haitian agriculture. After the 2010 Haiti earthquake, Winner championed the introduction of Monsanto hybrid seeds at cheap prices to Haitian farmers, despite the recommendation of the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture to halt all seed donations as both unnecessary and harmful. Winner undermines Haitian seed distribution networks, and will leave Haitian farmers dependent on Monsanto seeds when the program expires in 2015.

5. USAID ‘food aid’ is good for us agribusiness, not for Haitian farmers. Haiti’s domestic rice production was undermined even more by the vast amounts of ‘free’ American rice that USAID dumps on Haiti every year in the form of ‘food aid’. A recent report, ‘Sak Vid Pa Kanpe: The Impact of US Food Aid on Human Rights in Haiti’, explains how food aid is given to the poor as direct food assistance or sold by NGOs to support their overhead and operating costs, (a process known as ‘monetisation’). The report examines how US food aid benefits the American companies who provide and transport it, but has a negative impact on local Haitian economies which would benefit instead from agricultural assistance or cash to boost local production. In its most recent budget request, USAID proposed spending $1.2 billion globally on helping poor farmers grow more food, while asking Congress for $4.2 billion for food aid, almost all of which will be spent on purchases from American farmers.

6. USAID destroyed the Haitian creole pig. The 1982 swine flu outbreak in the Dominican Republic provided the justification for USAID to condemn Haiti’s 1.3 million pig population, promising to replace them with ‘better’ pigs. Over a period of 13 months, enforced by Duvalier militia, the Creole pig was wiped out. A Haitian woman recalls the era: ‘When the armed forces of Jean-Claude Duvalier’s regime set about exterminating Haiti’s Creole pigs, they would come to Haiti’s rural villages, seize all of the pigs, pile them up, one on top of the other, in large pits and set fire to them, burning them alive.’ In monetary terms Haitian peasants lost $600 million dollars. Haiti’s former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide analyzed the outcome in his book, ‘Eyes of the Heart’, explaining the small, black, Creole pig was at the heart of the peasant economy and constituted the primary savings bank of the peasant population. Pigs were sold to pay for emergencies, special occasions and to pay school fees and buy books for the children. What followed was a 30 per cent drop in enrollment in rural schools, a dramatic decline in protein consumption in rural Haiti, and a negative impact on the soil and agricultural productivity. When ‘better pigs’ arrived from Iowa two years later, they could not survive Haiti’s rural life, requiring clean drinking water (unavailable to 80 per cent of the Haitian people), imported feed (costing $90 a year when the per capita income was about $130), and special roofed pigpens.

7. USAID has consistently opposed minimum wage increases in Haiti. In 1991, USAID used US tax dollars to oppose a minimum wage increase from $.33 to $.50 per hour proposed by the Aristide government, claiming it was bad for business. The agency also countered a plan for temporary price controls on basic food so people could afford to eat. According to secret State Department cables, after the 2010 earthquake, the US Embassy in Haiti worked closely with factory owners contracted by Levi’s, Hanes, and Fruit of the Loom to block a small minimum wage increase for Haitian assembly zone workers, the lowest paid in the hemisphere. The factory owners, with backing of USAID and the US Embassy, refused to pay 62 cents an hour, or $5 per eight-hour day, a measure unanimously passed by the Haitian parliament in June 2009.

8. USAID promoted and funded the 2004 overthrow of the democratically-elected Aristide. While millions of American dollars have propped up Haiti’s dictators, aid shifted abruptly away from the democratically elected government of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Under the guise of ‘democracy promotion,’ USAID and USAID-funded organisations like the National Endowment for Democracy and the International Republican Institute, funnelled millions to organise political opposition to Aristide and build conservative alternatives aligned with US interests. After the 2004 coup, USAID funded the integration of former death squad forces into the Haitian National Police to quell resistance among Haitians to the illegitimate coup government. USAID paid millions to fund the fraudulent November 2010 and March 2011 elections that excluded Haiti’s largest political party, Fanmi Lavalas, the party of President Aristide.

9. USAID extends its far-reaching influence in Haiti by funding NGOs (non-governmental organisations) which receive 70 per cent of their budgets from the agency. Over 10,000 NGOs operate in Haiti with authorisation to bypass the elected government and serve as a permanent form of ‘soft’ invasion. As far back as 1995, Clinton’s Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott reassured members of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee that, ‘even after our (military) exit in February 1996 we will remain in charge by means of the USAID and the private sector.’

10. USAID boasts that 84 cents of every dollar of its funding in Haiti returns to the US in the form of salaries, supplies, consulting fees, and services. As the lead US agency for Haiti reconstruction, just 2.5 per cent of USAID’s $200 million in post-earthquake relief and reconstruction contracts had gone to Haitian firms by April 2010. USAID paid at least $160 million of its total Haiti-related expenditures to the Defense Department, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, two US search and rescue teams and, in at least two instances, itself. US Ambassador Merten reported to Washington that the post-quake ‘gold rush’ was on, according to a secret cable that described disaster capitalists flocking to Haiti for contracts to rebuild the country.

BROUGHT TO YOU BY PAMBAZUKA NEWS

* This article was first published by the Haiti Action Committee.

* Please send comments to editor[at]pambazuka[dot]org or comment online at Pambazuka News.

SOURCES:

– Aristide, Jean-Bertrand (2000). Eyes of the Heart: Seeking a Path for the Poor in the Age of Globalization. Common Courage Press, pp 13-14.

– Center for Economic and Policy Research (2010). Haitian companies bypassed in favor of DC area contractors with poor track records. Available at: http://bit.ly/sSyWoh (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Center for Public Integrity, Windfalls of War: Chemonics, International. Available at: http://projects.publicintegrity.org/wow/bio.aspx?act=pro&ddlC=8 (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Partners in Health, RFK Center for Justice & Human Rights (December 2010). Sak Vid Pa Kanpe: The Impact of US Food Aid on Human Rights in Haiti. Available at http://www.chrgj.org/projects/docs/sakvidpakanpe.pdf (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Coughlin, Dan and Ives, Kim (2011). ‘Wikileaks Haiti: Let them live on $3 day.’ The Nation, June 1, 2011. Available at: http://projects.publicintegrity.org/wow/bio.aspx?act=pro&ddlC=8 (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– DeWind Josh and Kinley David H (1994). U.S. Aid Programs and the Haitian Political Economy: Export-Led Development. IN The Haiti Files, Ridgeway J (ed). Essential Books/Azul Editions. Washington, DC. P125

– Diederich, Bernard and Burt, Al (2009). Papa Doc and the Tonton Macoutes, 3rd edition. Markus Wiener Publishers, Princeton, NJ.

– Doyle, Mark (Oct 2010) US urged to stop Rice Subsidies. BBC news, Latin America & the Caribbean. Available at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-11472874 (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Farmer, Paul (2006). The Uses of Haiti, 3rd edition. Common Courage Press.

– Flynn, Laura (Jan 2011). In Haiti, Reliving Duvalier, Waiting for Aristide. Huffington Post. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/laura-flynn/not-even-the-past_b_813172.html (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Gros, Jean-Germaine. Indigestible Recipe: Rice, Chicken Wings, and International Financial Institutions: or Hunger Politics in Haiti. Journal of Black Studies 2010 40: 974 originally published online 29 September 2008. Available at: http://jbs.sagepub.com/content/40/5/974.full.pdf (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Haiti Info (Sept 1995) Vol 3, #24. Neoliberalism in Haiti: The case of rice. Available at: http://www.afaceaface.org/blog/2010/09/neoliberalism-in-haiti-the-case-of-rice/ (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Hallward, Peter (2007). Damming the Flood. New York: Verso.

– Herz, Ansel and Ives, Kim (June 16, 2011). Wikileaks Haiti: The Post Quake Gold Rush for Reconstruction Contracts. The Nation. Available at: http://www.thenation.com/article/161469/wikileaks-haiti-post-quake-gold-rush-reconstruction-contracts (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Katz, Jonathan (March 2010). Haiti Relief Money: Criticism of Nonprofits Abounds. Huffington Post. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/03/05/haiti-relief-money-critic_n_487976.html (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Kurklantzick, Joshua. (Dec/Nov 2004). The Coup Connection. Mother Jones. Available at: http://motherjones.com/politics/2004/11/coup-connection (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– McGowan, Lisa (January 1997). Democracy Undermined , Economic Justice Denied: Structural Adjustment and the Aid Juggernaut in Haiti. The Development Group for Alternative Policies, Inc. Available at: http://bit.ly/tgmhpL (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– NACLA (1995). Haiti: Dangerous Crossroads. South End Press, Boston, MA. Chapter 19, p. 190

– Quigley, Bill (April 2008). Thirty years ago Haiti Grew All the Rice It Needed. What Happened? Counterpunch. Available at: http://www.counterpunch.org/2008/04/21/the-u-s-role-in-haiti-s-food-riots/ (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Smith, Ashley (24 Feb 2010). Haiti and the AID Racket. Counterpunch. Available at: http://www.counterpunch.org/2010/02/24/haiti-and-the-aid-racket/ (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Weisbrot, Mark (14 Oct 2010). CEPR Co-Director Criticizes US Funding of Flawed ‘Elections’ in Haiti. Press Release. Available at: http://bit.ly/uz3c3T (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Weisbrot, Mark (10 Jan 2011). Haiti’s Election: A Travesty of Democracy. The Guardian. Available at: http://bit.ly/tyqog0 (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

– Yaffe, Nathan. (June 2011) USAID’s Assault on Haitian Agriculture. Haiti Justice Alliance. Available at: http://haitijustice.wordpress.com/2011/06/21/winner-bad-for-haiti/ (Accessed Nov 10, 2011)

http://bolekaja.wordpress.com/2011/11/18/how-usaid-undermines-democracy-in-haiti/